Astronomers have taken a hard new look at how fast the universe is expanding and arrived at a disquieting conclusion. The latest observations from the James Webb Space Telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope agree with each other yet still clash with the leading model of the cosmos. The long-running discrepancy, known as the Hubble tension, has survived another round of checks and now points more clearly toward gaps in our understanding of the universe itself.

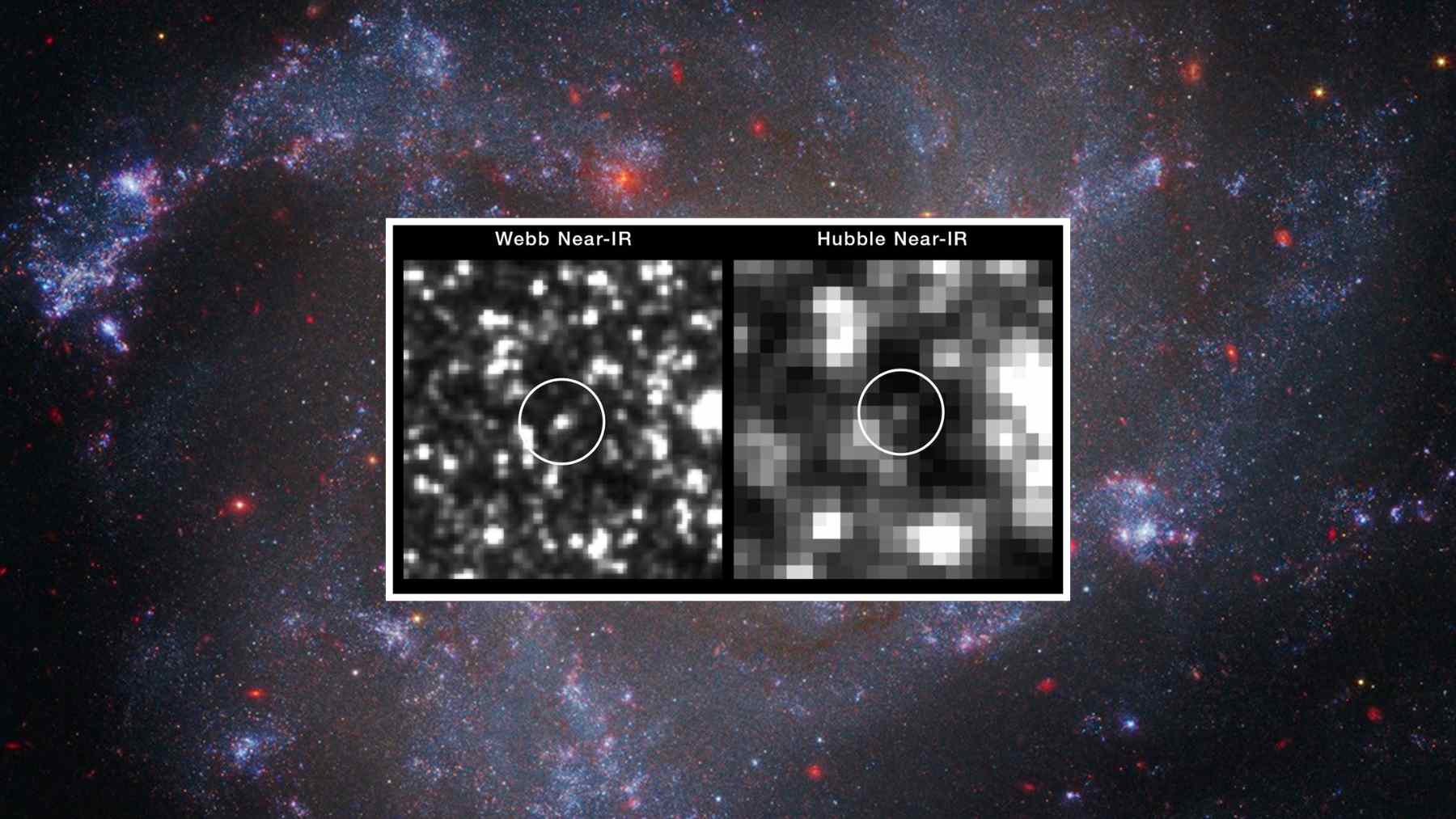

The new study, published in Astrophysical Journal Letters in February 2024, used Webb to re-observe more than one thousand Cepheid variable stars in six galaxies, including NGC 4258, a key anchor in the cosmic distance ladder. These stars had already been measured by Hubble. Webb’s sharper infrared vision let astronomers separate each Cepheid from nearby stars that might blur its light. The result matched Hubble’s distances almost perfectly, with an average difference of only about one hundredth of a magnitude.

“With measurement errors negated, what remains is the real and exciting possibility we have misunderstood the universe,” said lead author Adam Riess of Johns Hopkins University.

A universe that seems to expand at two speeds

At the heart of the problem sits a single number, the Hubble constant. It describes how quickly galaxies move away from one another as space itself expands. For more than a decade, two precise techniques have given answers that refuse to line up.

One method reads the afterglow of the Big Bang, the cosmic microwave background. The Planck satellite mapped tiny temperature ripples in this ancient light and, within the framework of the standard cosmological model, inferred an expansion rate of about 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

The second method builds a distance ladder in the nearby universe using standard candles such as Cepheid stars and type Ia supernovae. The SH0ES team, led by Riess, finds that nearby galaxies recede faster, at roughly 73 to 74 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

Both approaches are internally consistent. Both claim small error bars. Yet their answers differ by several kilometers per second per megaparsec, a gap large enough that random chance is unlikely to be the culprit. For cosmologists, that is like checking the household budget twice and still coming up short.

Webb checks Hubble’s homework

For years, one of the most down-to-earth explanations blamed Hubble itself. Because Hubble observes in crowded star fields, light from neighboring stars could sneak into its measurements of Cepheids and make them appear brighter and closer than they really are. If that effect grew with distance, it might artificially inflate the local expansion rate.

Webb was designed to test exactly this scenario. Its larger mirror and infrared capability produce sharper images, so individual stars stand out more cleanly in distant galaxies. In the new campaign, Webb revisited Cepheids in five supernova host galaxies out to about 130 million light years, plus the anchor galaxy NGC 4258.

The team found that Hubble and Webb distances agreed within a few percent across the full range of the ladder, ruling out hidden crowding as the source of the tension at more than eight sigma confidence.

In practical terms, the telescopes are telling the same story about how far away these galaxies are. The mismatch is not in the yardstick. It is in the underlying picture of the universe.

Hunting for missing physics

If the measurements hold, something in our cosmological model needs an update. Researchers have floated a variety of ideas, from slightly different properties of dark energy, to extra types of light particles in the early universe, to subtle tweaks in how gravity works on the largest scales.

So far, none of these proposals has won broad acceptance. Each must fit the Hubble tension without breaking the excellent agreement between theory and other observations, such as galaxy clustering and the detailed structure of the microwave background. It is a bit like adjusting one knob on a stereo only to find that it changes the sound of every instrument.

What this cosmic puzzle means down here

Most of us worry more about the electric bill than about expansion rates in units of kilometers per second per megaparsec. Does this cosmic crisis affect everyday life on Earth?

For the most part, no. Planetary orbits, satellite navigation and climate models rely on local physics that remains solidly tested. The tension lives on scales of millions or billions of light years. What the Webb and Hubble result really highlights is how science works when the numbers will not cooperate. The community checks instruments, repeats observations, and only then starts to question the underlying theory.

At the end of the day, that methodical approach is good news. It means our two flagship space telescopes are performing as advertised and that the universe is offering a rare clue that the standard picture, successful as it is, may be incomplete.

The next steps will likely involve even larger samples of galaxies, independent distance indicators, and new missions that probe the early universe in fresh ways. Until then, the Hubble tension remains, in Riess’s words, an exciting sign that there is still something fundamental left to learn about the cosmos we inhabit.

The study was published on the Astrophysical Journal Letters site.