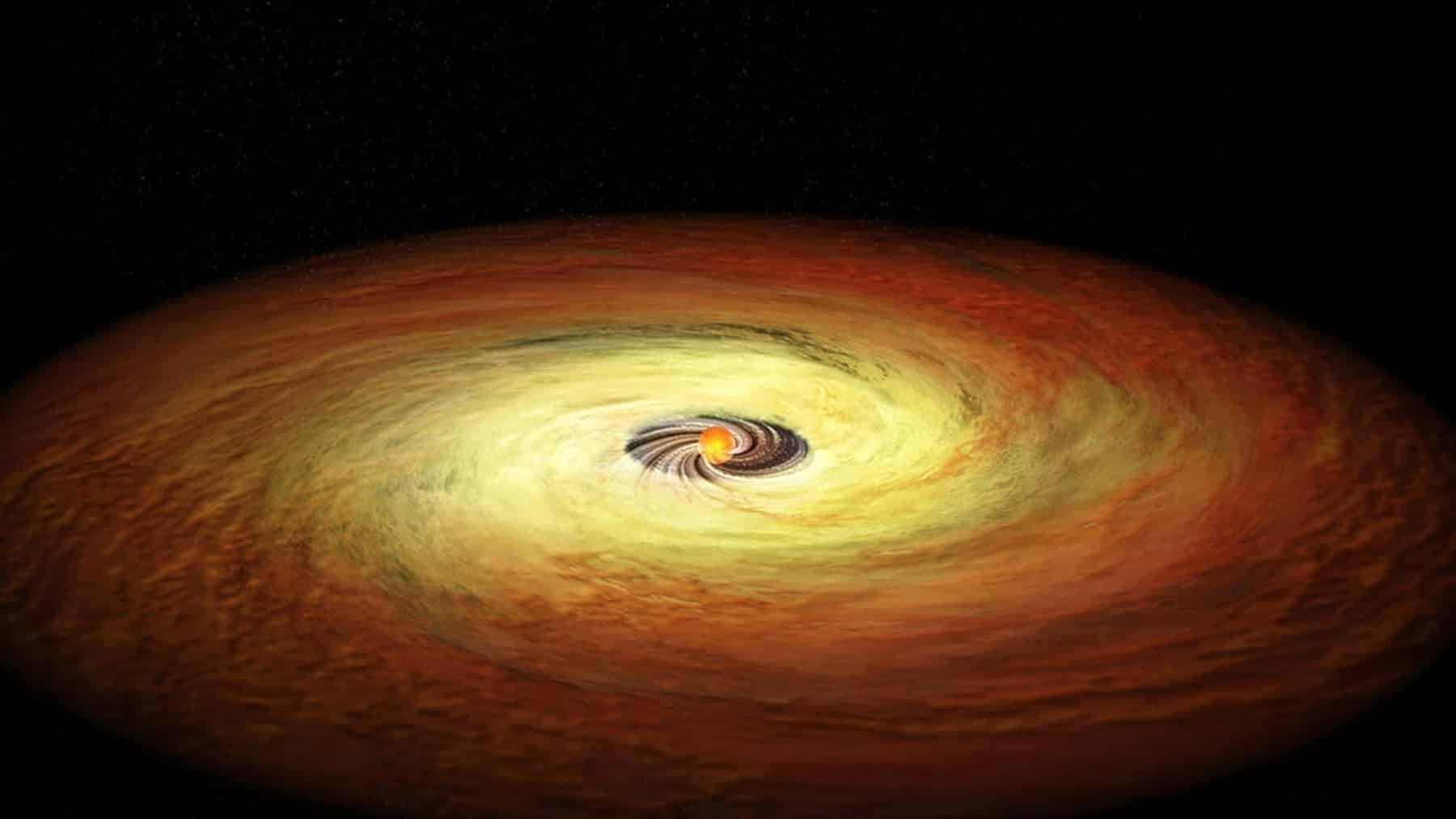

For a long time, we believed that the time it takes for planets to form was limited. We thought that protoplanetary disks, which are structures of gas and dust that surround young stars and serve as nurseries for new worlds, only lasted about 10 million years before dissipating into space. And is 10 million years a short time? In astrophysical terms, yes, it is a short time for planets to fully form. However, a recent discovery has shown that some disks can last up to three times longer than expected.

The discovery that changes our models

As is often the case with historic discoveries, NASA scientists did not expect to find a 30-million-year-old protoplanetary disk. In fact, they were simply observing a dusty, distant star system approximately 267 light-years from Earth with the James Webb Telescope. Suddenly, they came across this protoplanetary disk that is record-breakingly old and still rich in primordial gas: the type of raw material essential for forming planets.

After this discovery, which was based on the observation of a low-mass dwarf star known as J0446B, we realized that, by showing its great longevity, the study ended up contradicting everything we believed about the star’s radiation eventually dissipating the material in a few million years.

Of course, in addition to this new discovery testing our ideas, it also serves to demonstrate the chemical stability of the disk. This is because, even after tens of millions of years, the elements present in the system have not changed much, which can result in a stable environment that offers particles more chances to come together, form larger bodies, and, who knows, entire worlds.

Why does this news matter so much to us?

In addition to questioning our theories, this discovery has raised even more questions and speculations: What if long-lasting disks are the norm for certain types of stars? This could mean that planets like Earth could be forming in more places than we imagined. Let’s look at a real example to understand better:

The TRAPPIST-1 system, which is just 40 light-years from Earth, is a red dwarf star surrounded by seven planets, three of which are in the habitable zone, meaning that liquid water could exist there. And, well, until then, no one knew how such a compact system with such specific orbits had formed (a situation as strange as the discovery of this new planet in the solar system that shouldn’t exist).

Now, scientists have a new hypothesis: the planets of TRAPPIST-1 may have migrated slowly in a disk of gas that lasted longer than expected, and this movement would only be possible with the presence of gas, like that found in J0446B. These very long-lived disks may function as planetary assembly tracks that continue to operate, while the others may have already finished forming.

What else can we expect from this planet factory?

And as if this discovery wasn’t enough to shake up the world of astrophysics, scientists, observing a neighboring galaxy called the Small Magellanic Cloud, detected stars that were 20 to 30 million years old surrounded by planet-forming disks. What’s even more surprising is that this region had a low concentration of heavy elements, in other words, a situation very similar to what our universe was like right after the Big Bang.

This new discovery once again corrects our old beliefs that in these environments, the disks would dissipate too quickly to form large planets. What this study shows is that these disks not only survive longer, but they continue to be active, allowing the formation of planets, like this other planet factory found by NASA that could give us an answer about where we came from.