Imagine a small dark rock lying half buried in Antarctic ice. It looks unremarkable, yet scientists now think pieces like this could guide how we power and build our future in space. What if those frozen fragments turned out to be an early map of useful resources beyond Earth?

A new study of rare meteorites called carbonaceous chondrites suggests that some primitive asteroids hold useful amounts of water and metals. That could mean fuel, life support and basic construction materials for long missions without hauling everything from Earth.

Ancient rocks that never melted

Carbonaceous chondrites are fragments of undifferentiated asteroids that formed more than 4.5 billion years ago. Unlike larger bodies that melted and separated into core and crust, these small objects stayed mixed and primitive, locking in a record of the early solar system.

About five percent of meteorites found on Earth fall into this category, and many break apart, which makes the Antarctic finds valuable.

Josep M Trigo Rodríguez and his colleagues at the Institute of Space Sciences selected samples from six different chondrite groups linked to carbon rich asteroids, many of them recovered in Antarctica by NASA teams. In the lab, the researchers used highly sensitive techniques to measure dozens of elements.

Not all primitive asteroids are equal

The results show that these meteorites carry a complex mix of metals. Some groups, such as the CV and CK chondrites, are especially rich in titanium when compared with other carbonaceous chondrites. CR chondrites stand out for higher manganese levels.

When the team compared their measurements with typical rocks in Earth upper crust, they found that carbonaceous chondrites often contain more of many transition metals. At the same time, the abundance of rare earth elements was usually well below the levels that make a terrestrial deposit attractive to mine. The message is clear. Asteroids are interesting for metals, especially in orbit, but they are not magic treasure chests.

Co author Pau Grèbol Tomás summed up the challenge, saying that “studying and selecting these meteorites in our clean room is fascinating” but that most asteroids hold only small amounts of precious elements. Mining them at industrial scale would be a massive technical leap.

Choosing the right targets in space

Instead of treating every nearby rock as a prize, the team points to a few families that deserve closer study. K type asteroids that show absorption features from minerals such as olivine and spinel, and objects linked to CO and CV chondrites, appear especially promising because they seem to have kept much of their original metal in a relatively unaltered state.

For future missions, that kind of shortlist matters. Space agencies already plan sample return missions, and loose surface material on an asteroid, called regolith, is easier to grab than solid bedrock. Still, scaling up from a few kilograms of sampled dust to a real mining operation in microgravity is a completely different story.

That is where the environmental angle comes in. Co author Jordi Ibáñez Insa says that “the search for resources in space could help minimize the impact of mining activities on terrestrial ecosystems”. Open pits and the energy used to crush and refine ore all leave scars on landscapes. If some of that demand could eventually be met by materials already in orbit, it might ease pressure on fragile ecosystems.

Pathfinder for sustainable exploration

The researchers are careful not to oversell the idea. Their own data suggest that primitive asteroids will not outcompete the richest ore bodies on Earth. Water extracted on site could become rocket propellant or drinking water for astronauts. Metals could feed printers that build structures in orbit instead of shipping bulky parts from the ground.

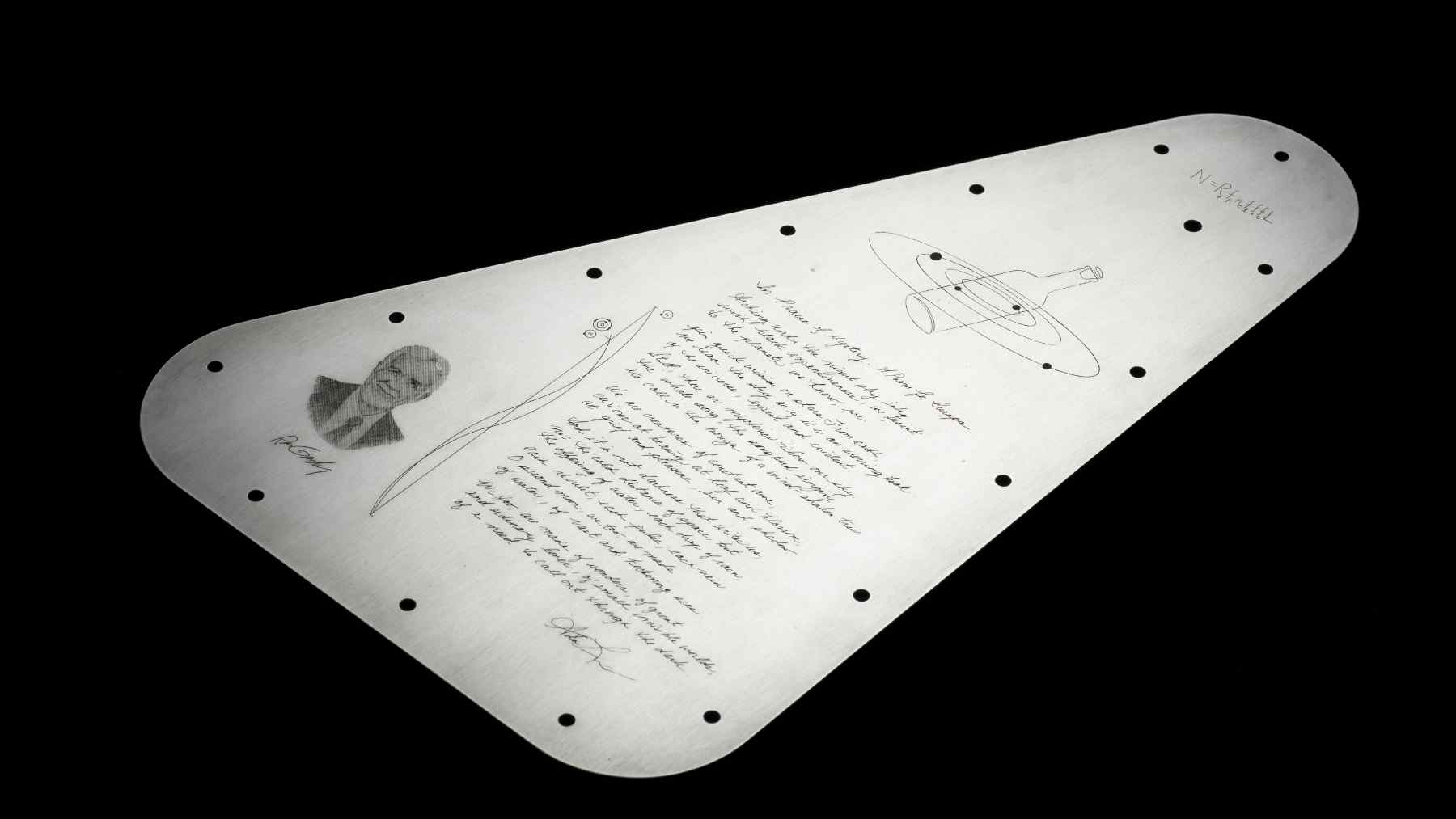

Sample return missions such as NASA OSIRIS REx and JAXA Hayabusa2 help connect specific asteroids to meteorite types studied in laboratories, giving mission planners a clearer picture of what different targets actually hold.

So that small stone in the ice is more than a curiosity. It is a quiet hint that the raw materials for a more sustainable space economy might already be drifting overhead, waiting for careful, science guided use rather than a new cosmic gold rush.

The study was published on Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.