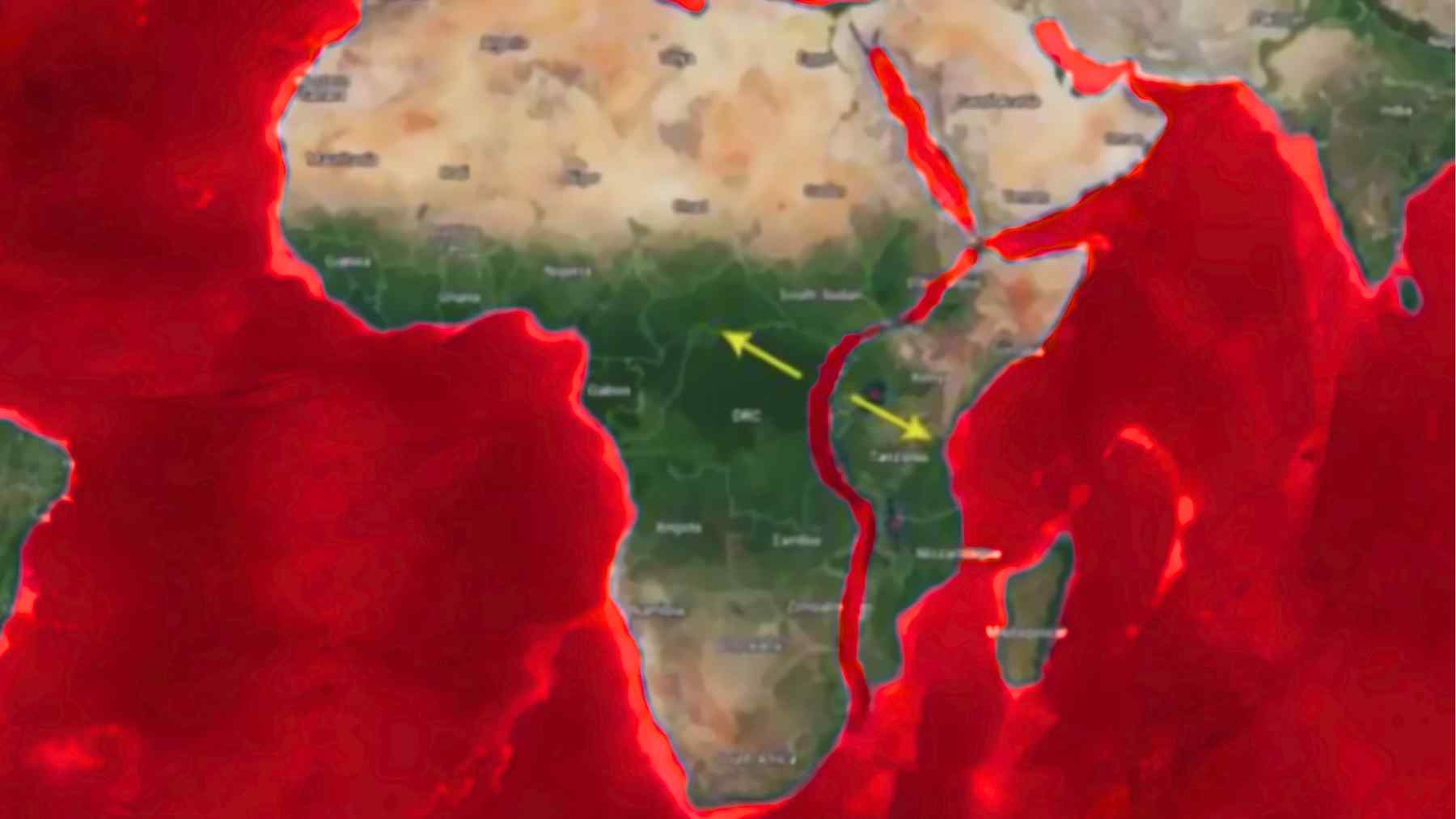

From space, Africa looks solid and immovable. On the ground, it is a different story. Along a scar known as the East African Rift System, the continent is literally pulling apart, and new research shows that the process is more focused and dynamic than scientists once thought. Over millions of years this slow stretch could open a new ocean basin and peel off part of East Africa into its own mini continent.

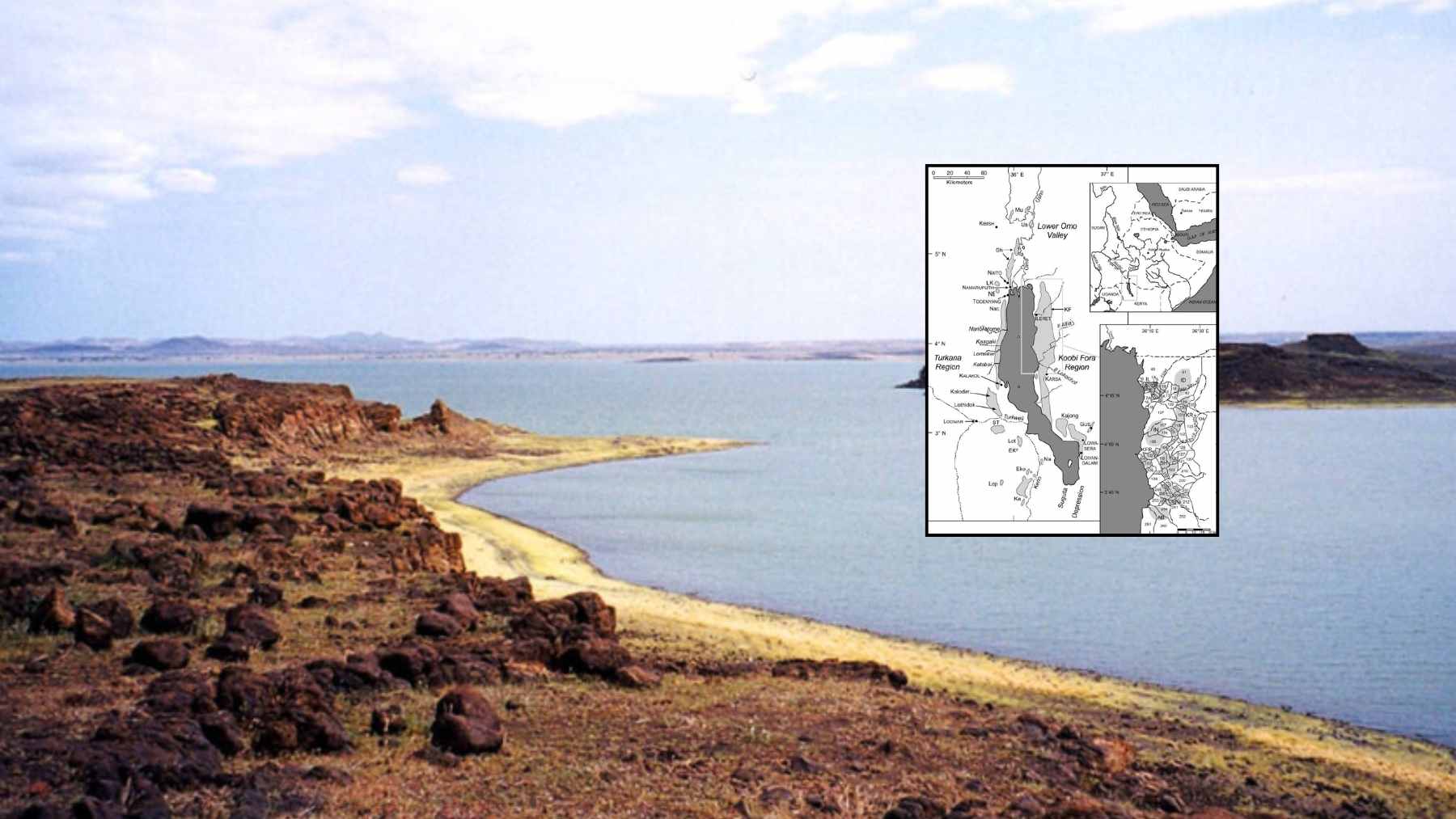

The East African Rift runs for more than 3,000 kilometers from the Afar Depression in northern Ethiopia through Kenya and Tanzania into Mozambique. It marks a developing plate boundary where the larger Nubian Plate is drifting away from the smaller Somali Plate, while the Arabian Plate moves off to the northeast. In everyday terms, Africa is being unzipped along a jagged line that satellites can already measure.

Afar, where three plates pull apart

The most dramatic action sits in the Afar region of Ethiopia. Here three rift arms meet (the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden and the Ethiopian branch of the East African Rift) and parts of the crust already resemble a young ocean floor. Much of Afar lies below sea level, dotted with active volcanoes and frequent earthquakes, making it one of the only places on Earth where mid-ocean ridge-style spreading can be studied in the open air instead of deep underwater.

From time to time, the planet puts on a show. In 2005, a crack about 35 miles long ripped open in the Ethiopian desert in just ten days when magma shoved two plates slightly farther apart. In 2018, intense rain in Kenya exposed a deep fissure that sliced through farmland and a busy highway, revealing one of the rift’s hidden fractures beneath people’s feet.

A geological heartbeat beneath Africa

What is powering this continental tear? A recent study in Nature Geoscience combined geochemistry and geophysics from more than 130 volcanic rock samples and found that a hot mantle plume beneath Afar rises in rhythmic pulses, described by some scientists as a kind of geological heartbeat. Those surges of magma weaken the crust under all three rift arms and help explain why some stretches are thinning much faster than neighboring blocks.

At the same time, new work in the journal Solid Earth maps thousands of faults and modern ground movements across Afar. The results show that strain has migrated toward the central rift axis, where magma softens and thins the crust. Together, these findings suggest that the ingredients for a future ocean crust are concentrating in a relatively narrow zone rather than spreading evenly across the region.

How fast will the new ocean form

When headlines say a “new ocean” is forming in Africa, it can sound like something you might sail across in your lifetime. The reality is far slower and also a bit more complicated. GPS data and seismic studies indicate that different parts of the rift are widening by a few millimeters each year, roughly the speed at which fingernails grow.

So when could seawater actually flood in? Estimates vary. Several recent summaries of the science place the birth of a true ocean basin somewhere between about five and ten million years from now for the Afar region, with full development into a sea comparable to today’s Red Sea possibly taking tens of millions of years. At the end of the day, researchers agree on one thing. The split is already under way, even if the final map lies far beyond human planning horizons.

Risk and opportunity along the rift

For communities from Ethiopia to Malawi, the important question is not what the coastline will look like in ten million years. It is how a restless rift affects daily life now. The same tectonic forces that create new valleys also generate earthquake swarms, ground sinking and sudden cracks that can damage homes, roads and water lines. Engineers in rift countries already repair warped highways and design new infrastructure with fault zones and soft ground in mind.

There is also a bright side. The heat driving this tectonic drama can be harnessed. In Kenya, geothermal plants along the Great Rift Valley tap underground reservoirs of hot water to produce electricity. Geothermal energy now supplies around forty percent of the country’s power in some recent years, helping cut fossil fuel use and keeping the lights on when hydropower dams face drought.

A living laboratory for continental breakup

Over far longer timescales, the eventual opening of a narrow ocean between the Nubian and Somali plates would create new coastlines, alter regional ocean currents and generate fresh marine habitats where there are now highlands and savannas. Scientists often liken the East African Rift to an early version of the Atlantic, giving them a rare chance to watch the early chapters of ocean formation instead of only reading the ending in ancient rocks.

So what should we take away when we see photos of those long fractures in East Africa’s crust? To a large extent, the message is that Earth is much more dynamic than the flat outline on a classroom wall. The same region that anchors some of the fastest growing cities on the continent is quietly rearranging itself on a planetary scale. Recent work on the Afar mantle plume and on how strain is focusing along the rift gives geologists a sharper picture of how that breakup is unfolding.

The study was published in Nature Geoscience.