On a calm September day in 2023, a remote fjord in eastern Greenland produced one of the strangest tsunamis ever recorded. When tens of millions of cubic meters of rock and ice crashed into Dickson Fjord, the impact raised a water wall around 200 meters (650 feet) high and set the planet ringing with a slow seismic hum that lasted more than a week. Scientists are now unpacking this event to better understand how landslides and tsunamis behave in a rapidly warming Arctic.

New analyses led by Angela Carrillo Ponce at the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences show that the landslide generated more than a single devastating surge. It created a long-lived standing wave, or seiche, that sloshed back and forth inside Dickson Fjord. That motion produced a very long period seismic signal that could be detected up to about five thousand kilometers away, turning the fjord into a natural laboratory for extreme waves.

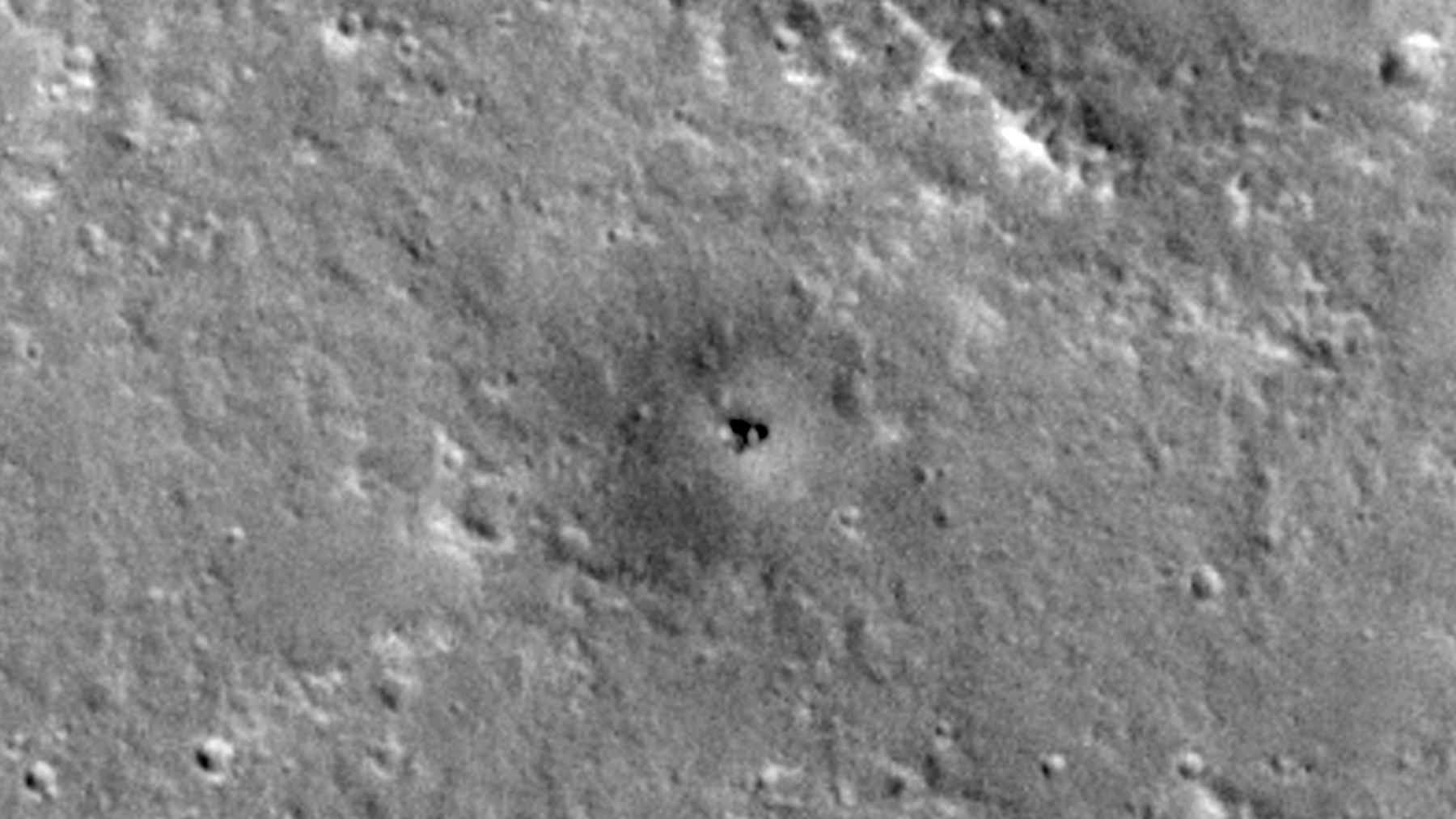

A rock and ice avalanche in Dickson Fjord

Satellite images and field work reveal that about 25 million cubic meters of metamorphic rock broke free from a slope more than one kilometer above the fjord. Halfway down, the collapsing mass slammed into a narrow glacier in a gully and transformed into a fast-moving mix of rock and ice. When that avalanche hit the deep water, it displaced enough seawater to generate a megatsunami with a runup exceeding 200 meters near the impact point and roughly 60 meters along a ten kilometer stretch of shoreline.

Global seismometers first registered a short, high-energy pulse from the landslide itself. Then a very different signal appeared with a much slower rhythm. Carrillo Ponce and colleagues interpret this second signal as the imprint of the seiche, a roughly meter high oscillation that bounced between the fjord walls for days. Independent satellite data from NASA’s SWOT mission later captured a tilted water surface inside the fjord, with one side sitting about 1.2 meters higher than the other, confirming the sloshing pattern.

From deadly 2017 tsunami to digital twins of fjords

Greenland has seen this kind of cascade before, with far more tragic consequences. In June 2017, a massive landslide in western Greenland’s Karrat Fjord generated a tsunami that raced down the fjord toward the village of Nuugaatsiaq. Waves there reached about one to one-and-a-half meters in height, flooding the shore up to nine meters above sea level, destroying homes and killing four residents. Near the source, surveys showed the wave had climbed around 90 meters on the impact side of the fjord and about 50 meters on the opposite shore.

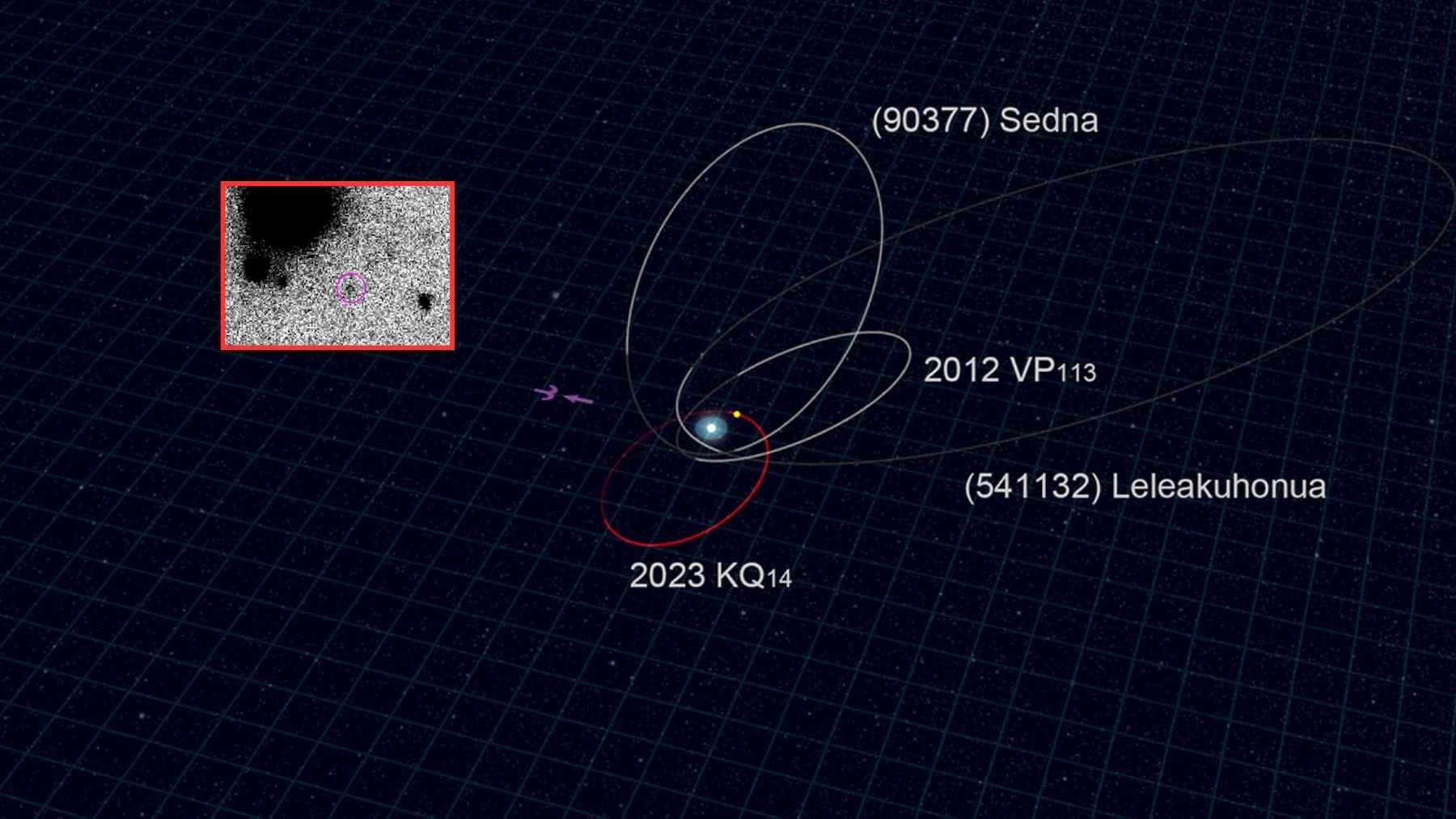

A new preprint on the Nuugaatsiaq disaster goes beyond describing what happened. Using seismic records from seven stations distributed across Greenland, Hideo Aochi and colleagues reconstructed the entire chain of events, from the landslide sliding into the fjord to the tsunami’s propagation and the tiny elastic flexing of the coastline as water levels rose and fell. Their simulations suggest that a one meter change in sea level can bend the surrounding ground by up to about a tenth to one millimeter, a signal that still appears on sensitive seismograms.

Seismology as an Arctic warning tool

Together, the Dickson Fjord and Nuugaatsiaq studies point to a powerful idea. In remote polar regions where there are no tide gauges, buoy networks, or dense coastal instrumentation, seismic monitoring can still reveal when a slope collapses, when a tsunami forms, and how large it is likely to be.

The new work shows that even without instruments on the shore, vibrations recorded inland and far away carry enough information to estimate landslide volume, tsunami height, and the timing of key stages in the cascade.

Climate change and unstable slopes

Researchers also warn that these are not isolated freak events. Greenland’s steep coastal mountains are held together in part by ice and permafrost. As the Arctic warms, glaciers thin and retreat, and frozen ground that once acted like cement begins to thaw.

Analyses of the 2023 Dickson Fjord collapse link the rockslide to glacial debuttressing, where the loss of ice support leaves oversteepened slopes more prone to failure. The 2017 Karrat Fjord tsunami has already forced evacuations in nearby settlements and sparked discussions about relocating exposed communities in western Greenland.