On a low hill in central Spain, near the Buendía Reservoir in Guadalajara, four nearly complete dinosaur eggs lay hidden in the rock for around 72 million years. They belonged to titanosaurs, giant long‑necked plant‑eaters that could grow over 80 feet long and weigh more than 60 tons, making them some of the largest land animals in Earth’s history.

Those eggs, now on display at the Paleontology Museum of Castilla-La Mancha (MUPA) in Cuenca, are part of a much larger nesting area at the Poyos fossil site. New research suggests this quiet Spanish hillside was once a crowded dinosaur nursery where more than one titanosaur species may have laid eggs side by side, a pattern almost never seen in the fossil record.

What scientists found on a hill in Guadalajara

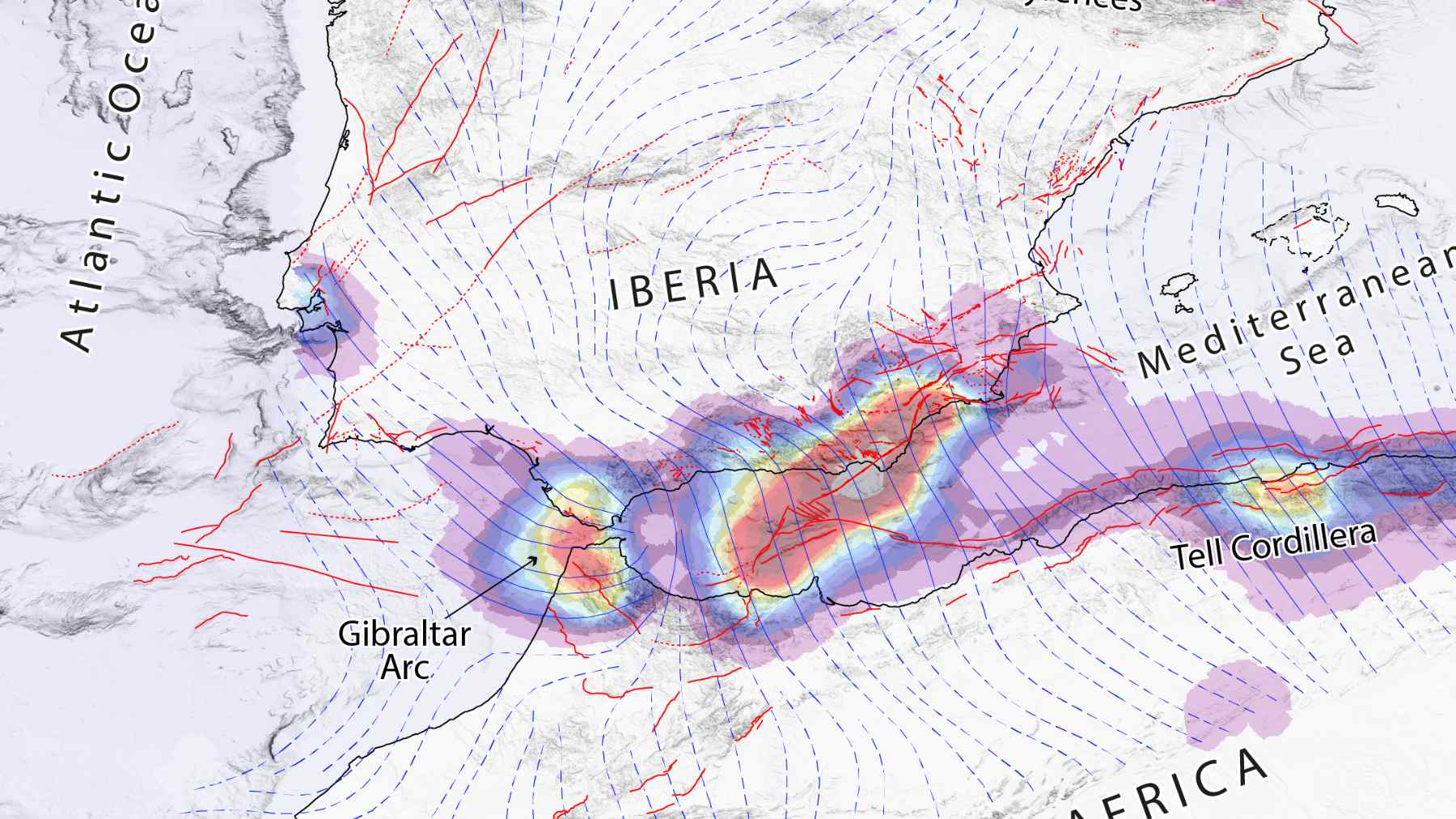

The Poyos site sits in rocks from the Villalba de la Sierra Formation, a geological unit that preserves some of the richest Late Cretaceous deposits on the Iberian Peninsula. Fossils from these layers show that, toward the end of the age of dinosaurs, this region was home to crocodiles, turtles, and several types of dinosaurs, including titanosaurs.

During recent digs, paleontologists uncovered multiple titanosaur egg clutches along different layers of sediment, as well as scattered eggshell fragments. Four of the best preserved eggs, roughly spherical and about as wide as a soccer ball, were selected for restoration and now form the centerpiece of the new MUPA display case.

For the Spanish team, led by Fernando Sanguino and Francisco Ortega from the Evolutionary Biology Group at Spain’s National University of Distance Education, Poyos quickly stood out as more than just another fossil site. Their detailed work shows that the area represents a vast titanosaur nesting ground from the late Campanian to early Maastrichtian stages of the Cretaceous, close to the final chapter before non‑bird dinosaurs disappeared.

Why these titanosaur eggs qre so unusual

When Sanguino and his colleagues looked closely at the eggshells, they realized they were not dealing with a single type of fossil egg. At least two different “egg types” are present: one assigned to a known group called Fusioolithus baghensis and another newly named form, Litosoolithus poyosi. In simple terms, the rock holds two distinct designs of titanosaur egg in the same layers.

Finding this kind of mix is extremely rare. The team notes that Poyos records only the second known case outside India where more than one fusioolithid egg type occurs together in the same nesting area. That unusual combination suggests that several titanosaur species, each with its own egg style, could have shared the same stretch of land to lay their clutches.

The new Litosoolithus poyosi eggs are especially striking. They are very large but have surprisingly thin shells and few pores, the microscopic openings that allow gas and moisture to pass through. Researchers think this odd mix of big size and delicate shell may reflect particular nesting conditions, for example soil that stayed humid enough that the embryos did not dry out even with fewer pores.

How researchers study fossil dinosaur eggs

Digging up dinosaur eggs is slow, careful work. At Poyos, the team mapped each egg and fragment in place, removed the surrounding rock bit by bit, and reinforced the fragile fossils with special glues before moving them to the lab and, for a lucky few, into the museum display. One wrong hit with a tool and a 72‑million‑year time capsule could crumble.

In the laboratory, scientists cut paper‑thin slices of eggshell and examine them under powerful microscopes. They measure shell thickness, pore shape, and crystal patterns, and they analyze the minerals that replaced the original shell during fossilization. Then they use statistics to compare those measurements with egg collections from India, South America, and other parts of Europe, deciding whether they match known types or represent something new.

A glimpse of life in the Late Cretaceous

The layout of the clutches at Poyos gives clues about how titanosaurs nested. Many eggs seem to have been laid in shallow pits and then covered with sediment, similar to nesting strategies seen at other titanosaur sites in Argentina and Brazil. That pattern fits the idea of large herds returning, season after season, to the same safe ground to reproduce.

Because Poyos lies in the southern Iberian Ranges, its fossils help link the Spanish record to other dinosaur sites in France and the rest of Europe. Studies of titanosaur bones from nearby Lo Hueco, along with the egg data from Poyos, suggest that Late Cretaceous Europe hosted a more diverse community of giant sauropods than experts once assumed, rather than a few isolated “island dwarfs” only.

From excavation site to museum exhibit

For visitors, the story now comes alive inside MUPA. The museum unveiled the eggs in a new display case during Science Week 2025, describing the find as a global reference point because it shows two different egg types sharing the same sediment level, something museum staff stress is extremely rare. Families walking through the galleries can see the real fossils just a few inches behind glass instead of only in textbooks.

The exhibit is part of a broader public project that includes school workshops, talks, and activities funded by regional science and heritage programs. In practical terms, that means students from Castilla-La Mancha can stand in front of the eggs, imagine the nesting ground that once covered their home region, and connect classroom lessons about extinction and climate to the rocks under their own feet.

At the end of the day, the Poyos eggs turn a handful of cracked shells into a detailed picture of dinosaur family life in Europe, just before everything changed 66 million years ago. The main study describing this discovery has been published in the journal Cretaceous Research.