China has become a powerhouse in the field of renewable energy, with a very strong commitment that began (you won’t remember) around the time of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. During these 16 years, they have been able to dominate photovoltaic, wind and even the dreaded and not-quite-clean nuclear. However, one revolution has escaped them, and it is the same one that we in America are pushing almost to the limit. They know it as the ‘fourth pillar’, and it is the one they are about to develop for the first time.

China dominates the 3 most powerful energy sources: The problem is this one

China is the global leader in hydrogen production, therefore, the country has encountered some major hurdles that may impede the production of green hydrogen. While it leads other clean energy segments, the country is currently being caught flat-footed to make similar inroads in this unfolding market.

China currently generates about 33 million metric tons of hydrogen every year, it is thus arguably ahead of the United States, which comes second on the list. Nevertheless, most of this hydrogen is referred to as “gray” hydrogen in as far as it is made using fossil fuels, particularly black coal and natural gas.

This process releases fairly considerable volumes of carbon dioxide, which is counterproductive given the fact that hydrogen was intended to be an environmentally friendly sources of energy.

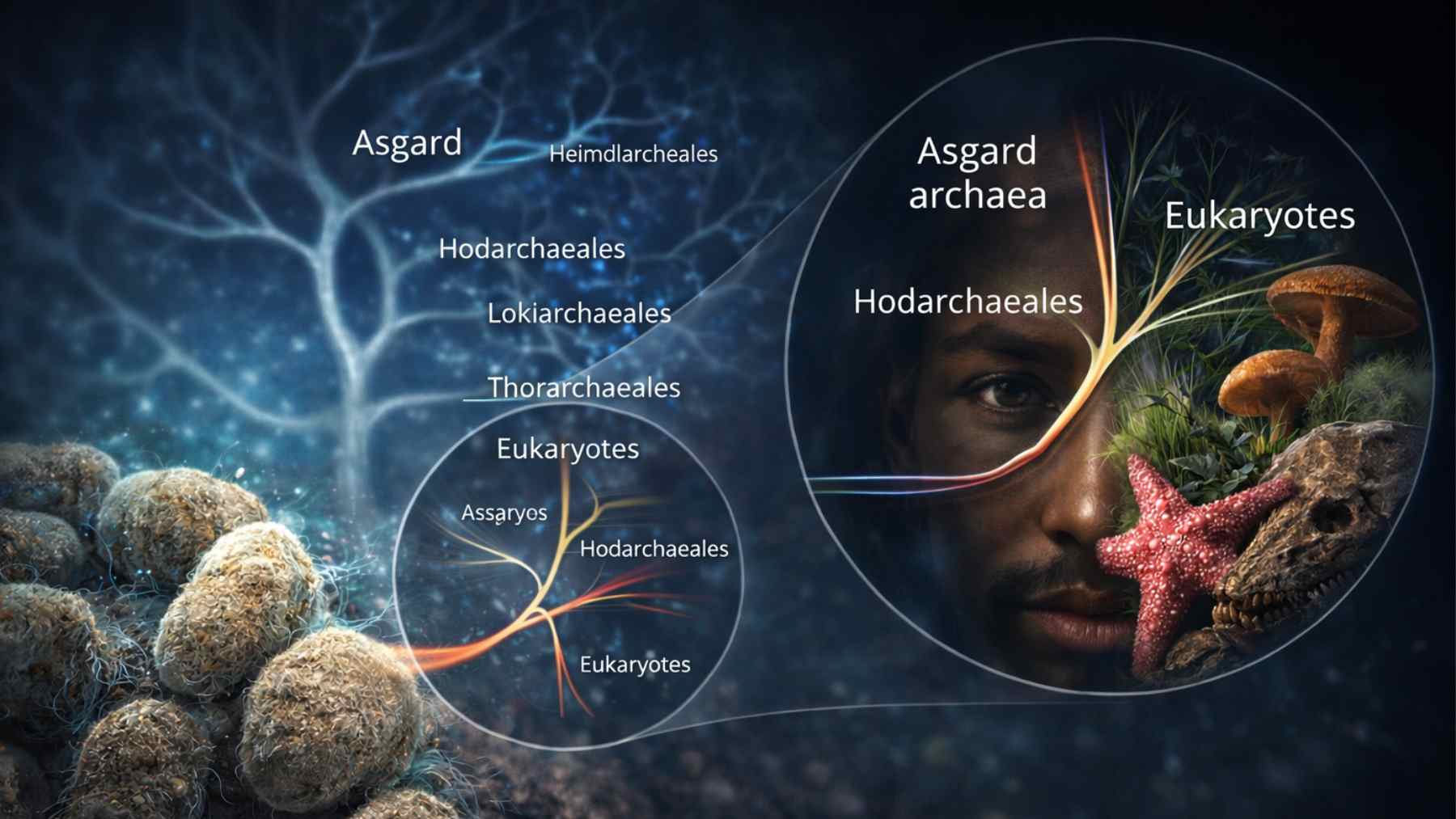

The breakdown of China’s hydrogen production is as follows:

- 80.3% from fossil fuels, especially from fossil methane sources, also known as gray hydrogen.

- 18.5% from industrial by-production

- 1.2% from electrolysis

- Less than 0.1%, which is produced by renewable energy-based electrolysis (green hydrogen).

Two keys to understanding Chinese hydrogen objectives

Still, the targets for green hydrogen production in China are much lower in comparison with other segments of clean energy:

- The National Development and Reform Commission revealed in March that the People’s Republic wants to generate up to 200,000 metric tons of green hydrogen annually within the next three years.

- These targets are far too low when compared to the levels of the United States and the European Union, which have targeted 10 million and 20 million metric tons by 2030.

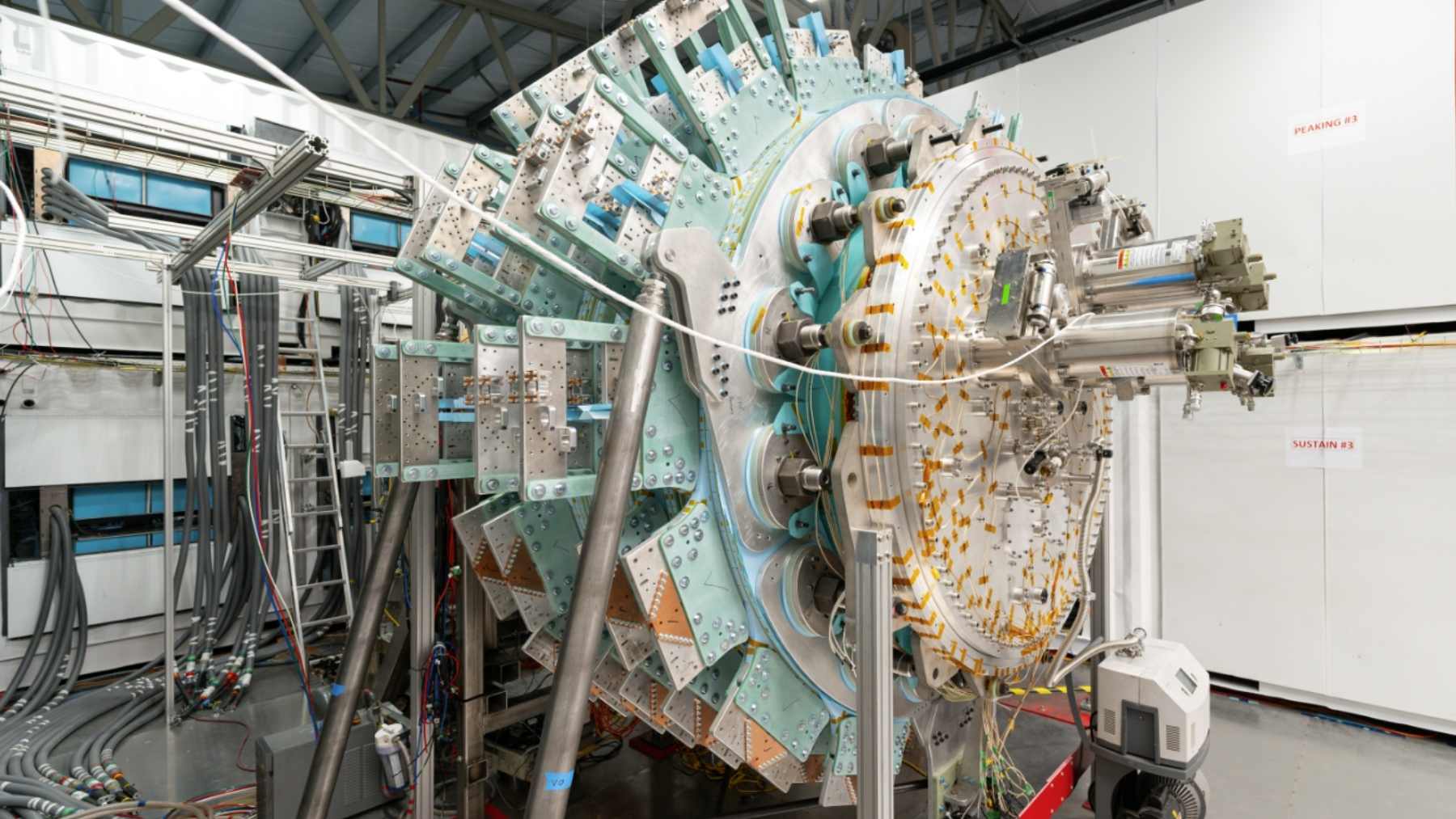

A leading Chinese project in green hydrogen is now experiencing enormous challenges. Sinopec, the state-owned oil and gas company, has stated problems at its Kuqa project in Xinjiang — the largest green hydrogen production site in the world — will not be fully addressed until, at least, late 2025.

The project was developed to go into operation in June 2023 with the following designed annual manufacturing capability of green hydrogen: 20,000 metric tons. However, some challenges have been encountered based on the operating equipment in the water electrolysis process and the fluctuations in the renewable power source.

The U.S. has SoHyCal, but China has Kuga: Why this project is not as promising as it seemed

The Kuqa project’s challenges highlight several key obstacles facing China’s green hydrogen industry:

- Technology gaps: Currently, Chinese firms are continuing to acquaint themselves with the higher-efficiency electrolysis that is essential in green hydrogen generation.

- Renewable energy integration: Solar and wind power are intermittent, which also translates into the production of hydrogen and creates a problem of consistency.

- Water scarcity: For several areas that are potentially good sources of renewable energy in China, including the Xinjiang region, water is a limiting factor, particularly where the water intensive electrolysis process is implemented.

- High costs: As already noticed, green hydrogen is much more costly than gray hydrogen, putting a brake on its widespread application.

China’s commitment to hydrogen is a demonstration of strength for the rest of the world, especially for emerging economies such as India. India installed the largest photovoltaic plant on the planet a few months ago, and now intends to make the leap to new energies. In America, meanwhile, we have been able to explore a complete ‘rainbow’ ranging from green to blue, passing through orange (and leaving aside gray or red, not good options).