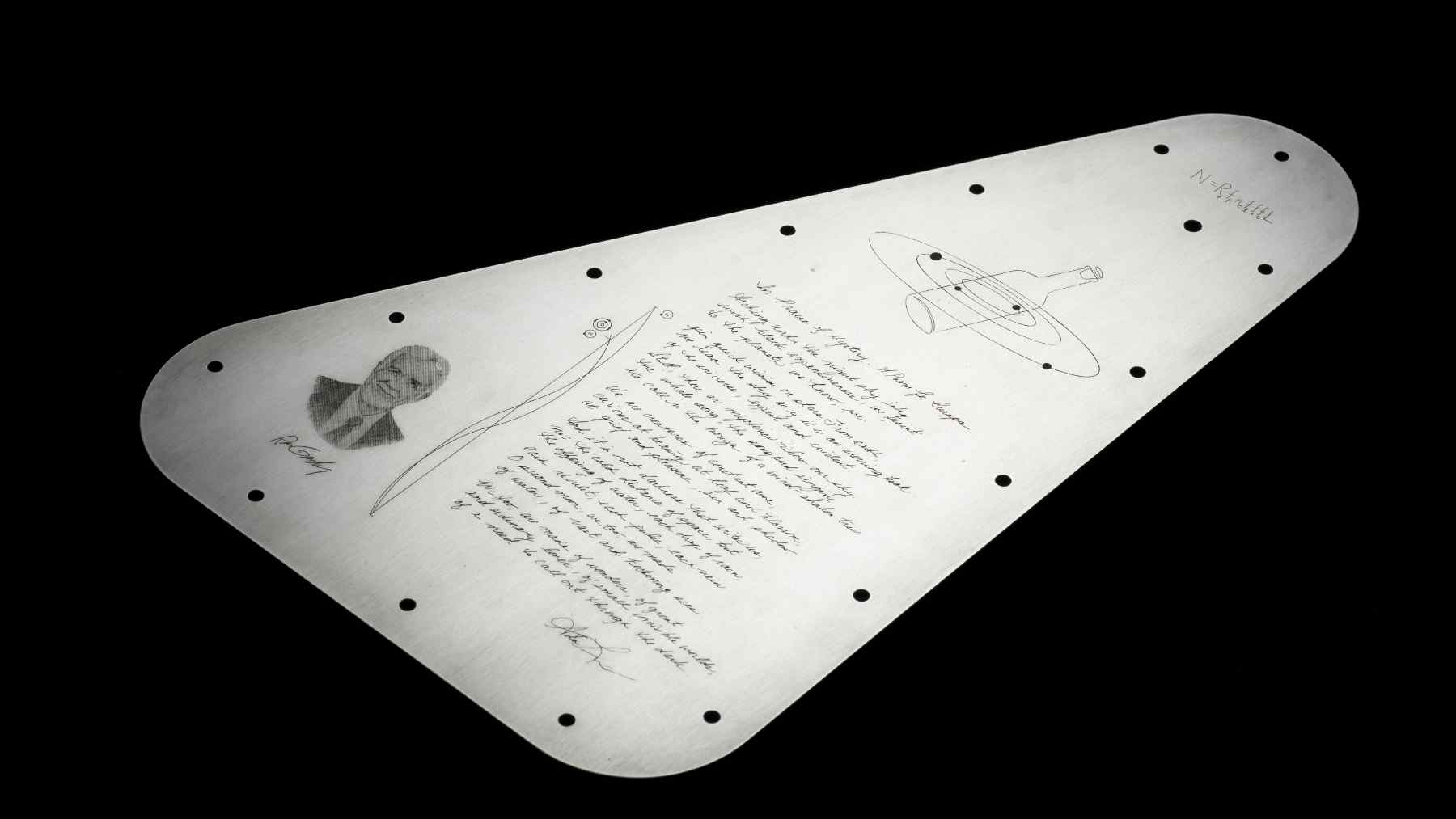

When NASA’s Europa Clipper left Earth in October 2024, it carried more than fuel, cameras, and radar. Bolted to the spacecraft is a thin triangular metal plate that holds millions of names, a handwritten poem, and carefully etched patterns for the word “water” in over one hundred languages. Together they form a modern echo of the famous golden records that left with the Voyager probes in the 1970s, this time aimed at a single ocean world orbiting Jupiter.

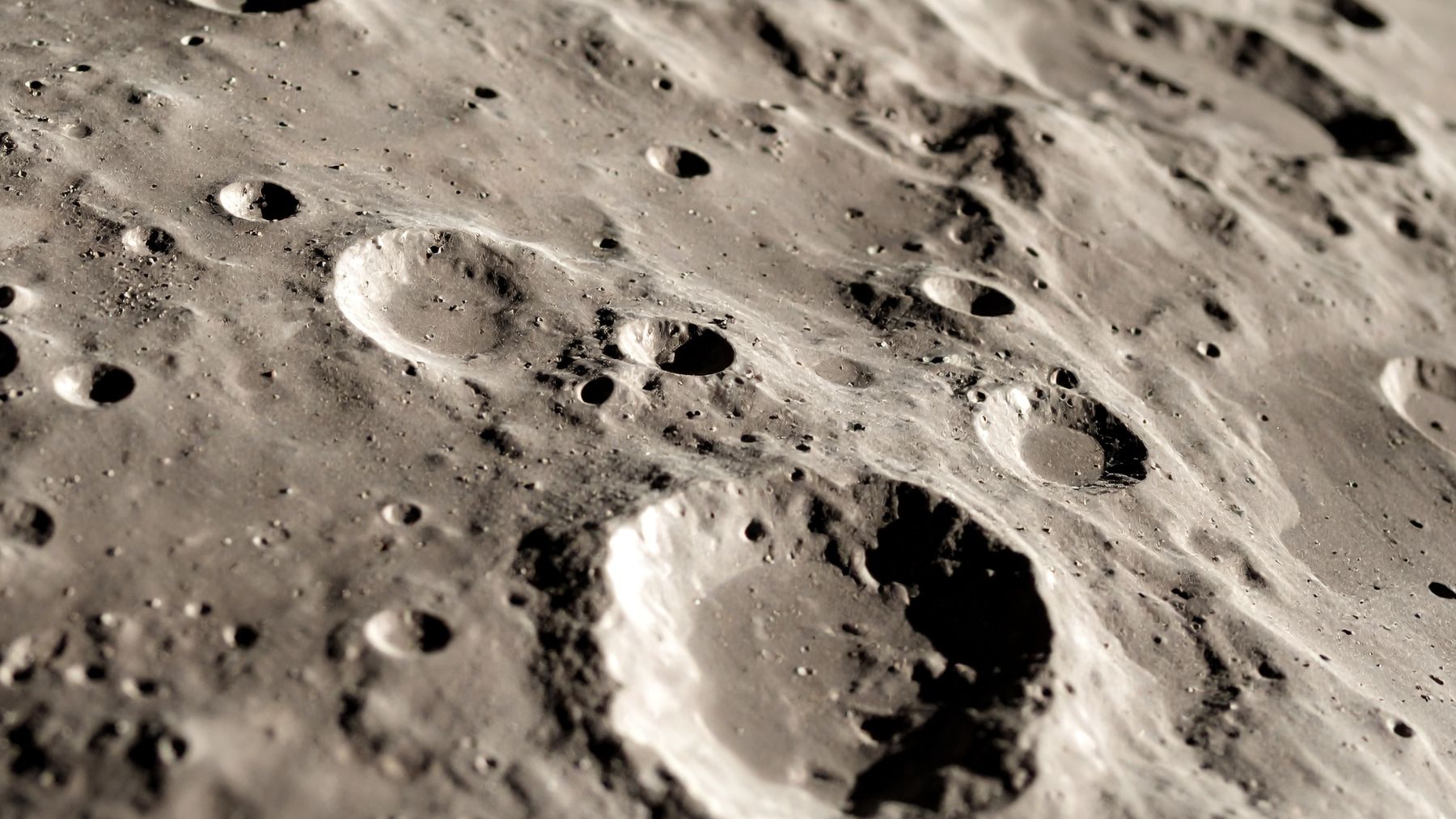

The destination is Europa, a frozen moon that almost certainly hides a global ocean beneath its cracked ice shell. NASA estimates that this hidden sea may contain more than twice as much water as all of Earth’s oceans combined, making Europa one of the most promising places in the solar system to look for habitable conditions.

A new golden record shaped by water

The plate that seals part of Europa Clipper’s radiation vault is made of tantalum, about a millimeter thick and roughly seven by eleven inches in size. It is mounted on the structure that protects the spacecraft’s electronics from Jupiter’s intense radiation, a practical shield that also carries a symbolic message.

On the inward-facing side sits a silicon chip stenciled with more than 2.6 million names collected through NASA’s “Message in a Bottle” campaign. Surrounding it is an illustration of a small bottle placed within the orbits of Jupiter and its four largest moons, a quiet nod to the idea that this spacecraft is delivering a message across the dark.

Next to the chip is U. S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón’s original work “In Praise of Mystery, A Poem for Europa,” engraved in her own handwriting. Close by, the Drake Equation appears in the script of astronomer Frank Drake, honoring decades of scientific debate about how common advanced civilizations might be in our galaxy. An additional motif shows the “water hole” radio frequencies linked to hydrogen and hydroxyl, a quiet reference to how scientists listen for signals in space using the chemistry of water.

The outer side of the plate is even more explicitly about water. Linguists gathered recordings of the word “water” from language families around the world. Those sounds were converted to waveforms and etched into the metal so that curved lines ripple outward from a central symbol representing the American Sign Language sign for water. NASA describes this design as “Water Words,” a visual map of how every culture depends on the same simple molecule.

As Lori Glaze, who directs NASA’s Planetary Science Division, put it, “The content and design of Europa Clipper’s vault plate are swimming with meaning.” Project scientist Robert Pappalardo adds that the team has “packed a lot of thought and inspiration into this plate design” and into the mission as a whole.

Two oceans, one fragile home

Europa Clipper’s main science goal is straightforward to describe but difficult to answer. The mission will perform nearly fifty close flybys of Europa, sometimes swooping only about sixteen miles above the ice, to find out whether there are places below the surface that could support life. Instruments on board will map the ice shell, probe the subsurface with radar, analyze the chemistry of the surface and thin atmosphere, and look for signs that material from the ocean reaches the surface or escapes in plumes.

Recent observations from the James Webb Space Telescope have already detected carbon dioxide in a specific region of Europa’s surface. Studies suggest that this carbon likely rose from the subsurface ocean rather than arriving with meteorites and that it was delivered on a geologically recent timescale. For astrobiologists, that combination of carbon, liquid water, and energy from tidal heating makes Europa a compelling natural laboratory.

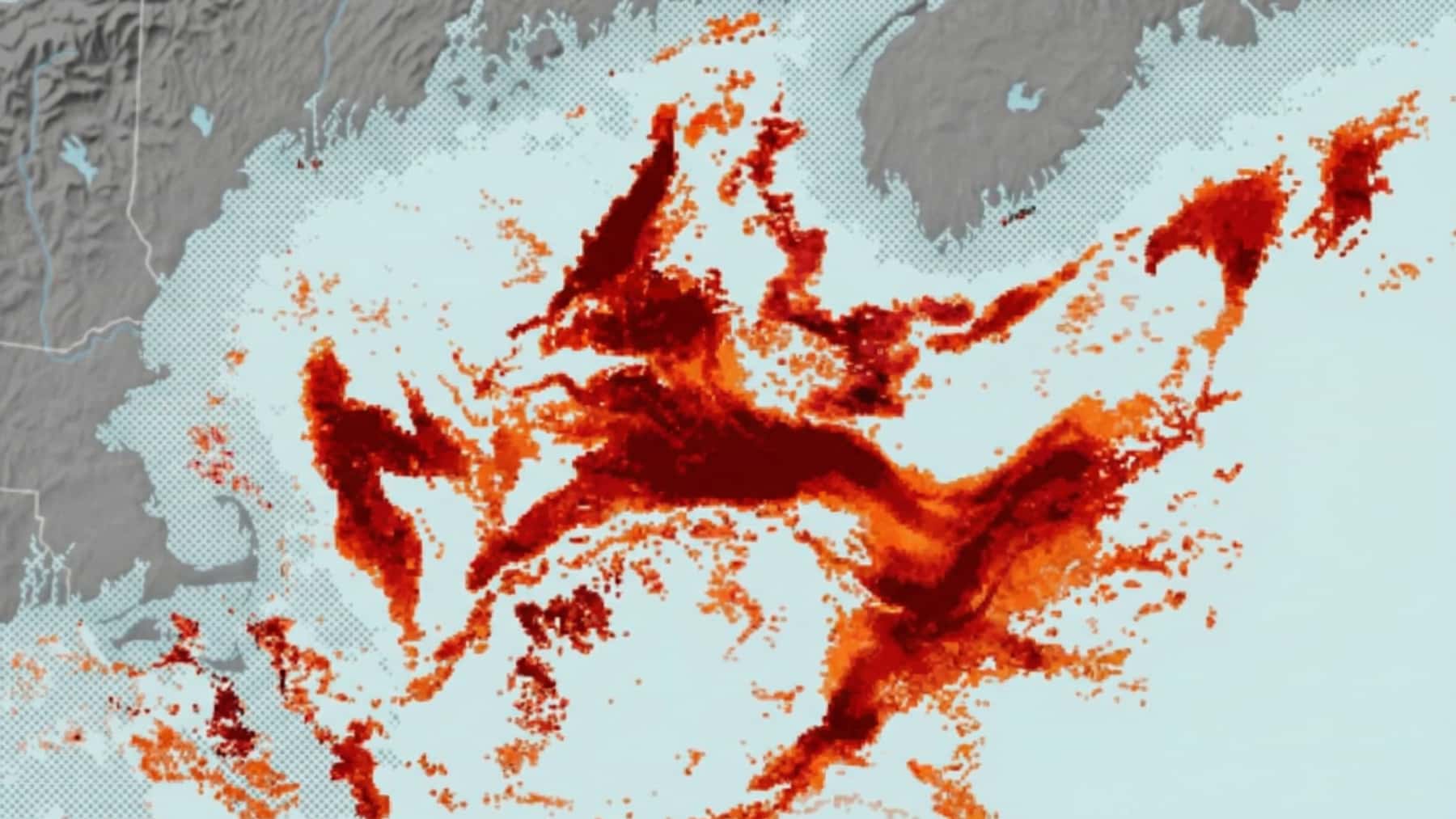

Yet the plate’s focus on water is not only about a distant moon. On Earth, the global ocean covers about 71 percent of the planet and contains roughly 97 percent of all water. It supplies most of the habitable volume for life and supports close to half of global primary production.

Scientists estimate that about half of the oxygen in the air we breathe comes from microscopic plankton that float near the ocean surface. The seas have also absorbed more than 90 percent of the excess heat trapped by human greenhouse gas emissions, buffering the atmosphere but driving marine heatwaves, acidification, and shifts in marine ecosystems.

In other words, the same element that makes Europa interesting is the one that regulates our climate, shapes our weather, and fills the glass of water on a kitchen table.

A mission that looks outward and inward

By the time Europa Clipper arrives in the Jupiter system around 2030, public attention may focus on the first close-up images of Europa’s fractured plains and possible geysers. Researchers hope to learn how thick the ice shell is, how salty the ocean might be, and whether the chemistry in that sea could support life based on known principles.

At the same time, the small plate riding on the spacecraft invites a quieter reflection. It links our changing blue planet to a distant icy ocean, reminding us that liquid water is rare in the solar system and essential wherever it is found. As humanity sends a carefully engraved word for “water” into deep space, the harder work remains at home, where Earth’s own oceans are warming and absorbing pollution.

Europa Clipper will not answer every question about life beyond Earth. For the most part, what it offers is a sharper picture of what an alien ocean really looks like. The plate on its side simply adds a human footnote, a message that says we understood what was precious here and tried to carry that understanding outward.

The official statement was published on NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory website.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.