Heart doctors are no longer guessing what is happening inside clogged heart arteries. They are sliding tiny cameras into those arteries and watching, almost like live videos, as powerful cholesterol drugs go to work.

A new scientific review of several major trials finds that a class of medicines called PCSK9 inhibitors, when added to standard statin drugs, can make dangerous fatty plaques in heart arteries smaller and more stable in about a year. These changes show up directly on the inside-wall images, not just on blood tests, which helps explain why these drugs lower the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

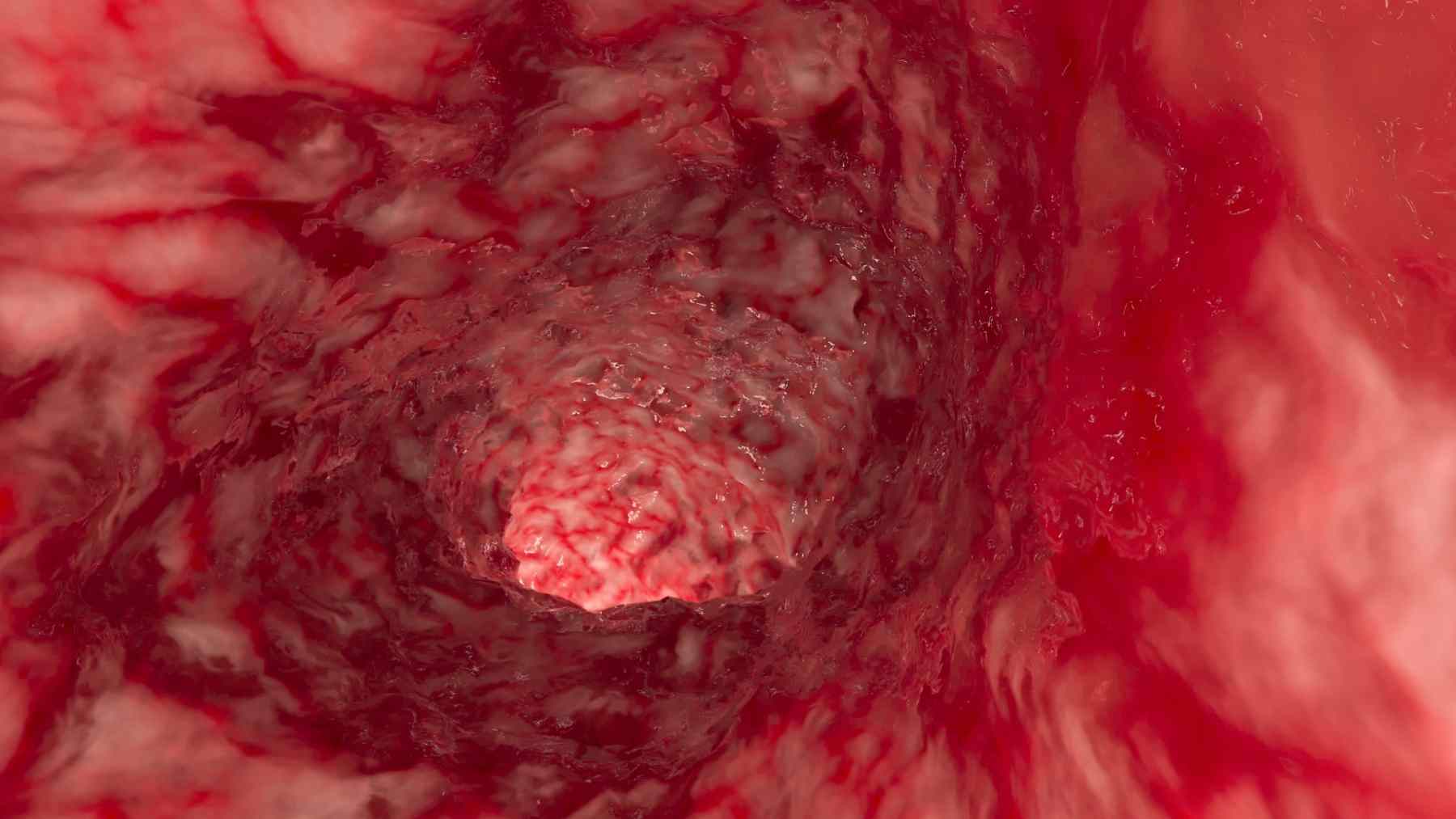

What doctors can now see inside heart arteries

For years, cardiologists had to rely on angiograms, dye pictures that only outline the hollow center of an artery. Those images show where the artery is narrow, but they do not reveal what is hiding inside the wall where plaque builds up.

The new review pulls together studies that used invasive imaging, meaning a thin tube with sensors goes right inside the artery. These studies tracked the same spots in the same arteries before and after treatment with PCSK9 drugs, so doctors could see whether plaques were shrinking or changing their structure over time.

Teams at large hospitals in Europe and North America combined their data. Together, they followed hundreds of patients who were already on strong statins and then received extra PCSK9 medicine, giving a much clearer picture of how these drugs remodel plaque deep in the heart.

How PCSK9 drugs help clean up bad cholesterol

Most people have heard of “bad” cholesterol, or LDL. This fatty substance travels in the blood and can get stuck in artery walls, slowly forming a lump of fat, cholesterol crystals, and scar tissue called plaque. When plaque grows or ruptures, it can block blood flow and cause a heart attack.

Statins are the first line of defense. They lower LDL and clearly cut the risk of heart attacks and strokes, but many high risk patients still have trouble even when their lab numbers look decent. PCSK9 inhibitors step in here, helping the liver pull even more LDL out of the bloodstream, so LDL levels drop to values many people never reach with statins alone.

In a major outcomes trial called FOURIER, adding the PCSK9 drug evolocumab to statins pushed average LDL down to about 30 milligrams per deciliter and reduced serious heart problems in high risk patients. That success raised a big question: are patients safer only because of better numbers on paper, or because plaque inside the arteries is actually healing and calming down.

Tiny cameras that ride inside the arteries

To answer that question, researchers turned to new imaging tools that work from inside the artery itself. One tool, intravascular ultrasound, uses sound waves from a catheter to draw a cross section picture of the artery wall, letting doctors measure how much space plaque takes up, not just how wide the opening is.

Another tool, optical coherence tomography, uses light instead of sound. It gives very sharp images of the thin “cap” of tissue that covers the soft, greasy core of a plaque. A very thin cap is fragile and more likely to tear, so watching that cap get thicker is like seeing a cracked sidewalk get a fresh layer of concrete.

A third method, near infrared spectroscopy, reads how plaques absorb light to estimate how much oily lipid is inside. When doctors combine these approaches, they can tell how big the plaque is, how it is built, and how much of it is made of dangerous soft fat versus tougher, more stable tissue.

Big trials that watched plaques change in real time

One key study in the review is called GLAGOV. Nearly 1,000 patients on statins had ultrasound images taken inside their coronary arteries, then were randomly assigned to receive evolocumab or placebo, and imaged again after about a year and a half. Patients on evolocumab showed a clear drop in how much of the artery wall was filled with plaque, and more than half had actual plaque shrinkage instead of continued growth.

Another trial, HUYGENS, looked at people who had a type of heart attack known as non ST elevation heart attack. With repeated OCT and ultrasound scans, researchers found that evolocumab on top of statins thickened the protective cap and reduced the arc of fatty material inside plaques when compared with placebo, signs that the plaques were becoming harder to rupture.

The PACMAN-AMI trial tested the PCSK9 drug alirocumab in about 300 patients after a classic heart attack treated with a stent procedure. Using several imaging methods in arteries that had not caused the original heart attack, researchers saw that alirocumab plus high intensity statins shrank overall plaque burden, cut down the lipid rich core, and increased cap thickness within one year.

In the ARCHITECT study, more than 100 people born with very high cholesterol, a condition called familial hypercholesterolemia, received alirocumab on top of strong statins. Noninvasive coronary CT scans over about a year and a half showed that total plaque burden dropped and the mix of tissue shifted away from soft, unstable material toward more fibrous and calcified, and therefore more stable, plaque.

Why calmer plaque may cut future heart attacks

Cardiologists pay close attention to certain warning signs inside a plaque. A large oily core, a very thin protective cap, high inflammation, and weak scar tissue are all clues that a plaque might split open and suddenly form a clot. Many of these risky plaques do not cause a major blockage on the usual angiogram, so they can sit quietly for years before causing trouble.

Across the imaging trials, PCSK9 inhibitors tended to push plaques away from that “troublemaker” pattern. Plaques became slightly smaller, held more fibrous tissue, contained less loose cholesterol, and were covered by thicker caps that are less likely to tear. In simple terms, the drugs seem to help turn a wobbly mud pile into something more like a solid speed bump.

These shifts match what doctors expect when LDL stays very low for a long time. By following the same artery segments over months, the studies directly link big drops in LDL with physical signs of plaque healing, which supports the better outcomes seen in large PCSK9 trials.

What it could mean for patients and doctors

The imaging work is changing how experts think about coronary disease. Instead of caring only about how narrow an artery looks, they are learning to care just as much about what kind of plaque is sitting in the wall and how “angry” or calm it appears. A mild narrowing made of soft fat with a thin cap may be more dangerous than a tighter narrowing made of tough fibrous and calcified tissue.

Researchers are also testing whether less invasive scans, such as advanced CT, can pick out people whose plaques still look risky even when regular tests seem fine. If that works, doctors could someday match PCSK9 treatment not only to cholesterol numbers but also to the hidden biology of each patient’s plaque. That might help decide who really needs these drugs, which are still expensive and mostly used in very high risk patients.

Ongoing trials are asking how early and how aggressively to use PCSK9 inhibitors after a heart attack and whether imaging measurements should help guide future treatment guidelines. For now, the message is simple enough: in the right patients, these medicines do not just make lab reports look better, they help heal the damage that doctors can now see inside the heart’s own plumbing.

The study “PCSK9 and coronary artery plaque: new opportunity or red herring?” has been published in Current Atherosclerosis Reports.