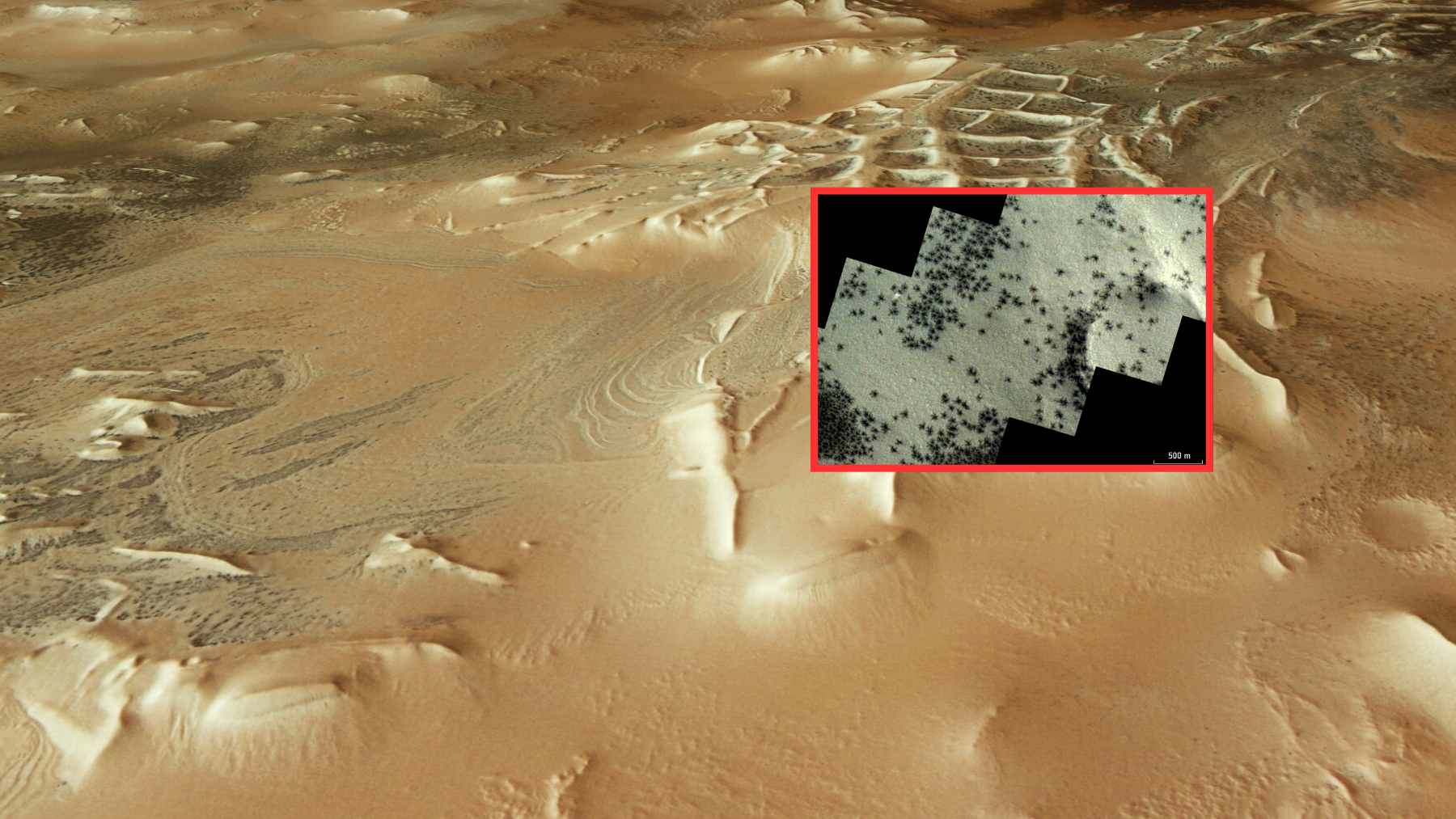

Every spring on Mars, hundreds of dark blotches appear around a strange grid of ridges near the south pole. From orbit they look uncannily like swarms of spiders racing across pale sand. In reality they are one of the most dramatic seasonal events in the solar system, and fresh images from the European Space Agency show that spider season in the region nicknamed Inca City has begun again.

These “spiders” are not living creatures. They are the scars left behind when carbon dioxide gas bursts through a winter blanket of dry ice that covers Mars’s southern polar terrain. During the long polar night, carbon dioxide from the thin atmosphere freezes onto the ground in layered slabs that can reach about one meter in thickness in places.

When sunlight returns in spring, it shines through the translucent ice and warms the darker soil below. That warmth turns the bottom of the ice directly into gas, a process scientists call sublimation. Gas accumulates under the slab until the pressure finally wins. It finds weak spots, cracks the ice and rushes upward, dragging dust and sand with it.

Seen from above, each eruption sprays a dark fan onto the surface and leaves a spot between about forty-five meters and one kilometer wide. Over many seasons, the escaping gas also etches a branching network of shallow troughs in the ground. Planetary scientists refer to these patterns as araneiform terrain, from the Latin word for spider. They note that this is a Martian specialty with no direct equivalent on Earth.

Why is Mars so good at making spiders while Earth is not? The answer lies in the planet’s atmosphere. Mars’s air is dominated by carbon dioxide and a significant fraction of that gas freezes out onto each winter pole. Studies of polar ice and gravity show that roughly a quarter of the Martian atmosphere can be locked up in these seasonal caps before returning to the air in spring.

That waxing and waning turns carbon dioxide into the most active volatile substance on Mars today. As it cycles between gas and ice, it lifts dust, sculpts pits and grooves and drives the geysers that create the spiders. Researchers argue that this seasonal carbon dioxide system is now one of the main forces reshaping the Martian surface.

The new images focus on Inca City, a compact maze of straight ridges whose geometric layout reminded early observers of Andean ruins. The structure sits near the south polar layered deposits and is more formally known as Angustus Labyrinthus. It was first spotted in the 1970s by NASA’s Mariner 9 spacecraft.

Exactly how those “walls” formed is still debated. High-resolution mapping shows that they follow part of a circle about 86 kilometers across. Many researchers now suspect the circle is an ancient impact crater whose fractures later filled with rising lava. Over time, softer surrounding material eroded away, leaving the harder ridges standing. Other ideas involve fossilized sand dunes or glacial landforms known as eskers.

Whatever their origin, the ridges are now dotted and surrounded by the new dark spots. ESA’s Mars Express camera sees the blotches sprinkled over hills, plateaus and mesas, while the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter images the spider-like channels lurking beneath the ice itself. Together, the two orbiters show both the fresh surface stains and the older subsurface web that feeds them.

On Earth, the closest everyday comparison might be the way frost disappears from a car windshield on a bright morning, only with far more violence than anything in a suburban driveway. Laboratory work has now backed up this picture. Experiments at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory recently recreated miniature spiders in a chamber that mimics Martian polar conditions, using carbon dioxide ice and powdered soil. The tests produced gas plumes and crack patterns that matched those seen from orbit, lending strong support to the carbon dioxide jet model.

“The spiders are strange, beautiful geologic features in their own right,” said planetary scientist Lauren Mc Keown, who led the lab study. She and other researchers see them as more than a curiosity. They are a natural experiment in how a greenhouse gas can freeze, flow and erode a landscape when an entire quarter of the atmosphere migrates from sky to ground and back again every year.

For climate scientists, that makes Mars a powerful comparison case. On Earth, carbon dioxide stays in the air and traps heat, affecting everything from crop yields to the summer air conditioning bill. On Mars, the same molecule acts more like a sculptor’s tool, carving spider webs into frozen ground and quietly recording the rhythm of the planet’s seasons.

The latest views of Inca City do not reveal life, but they do reveal a living planet in another sense. Mars’s surface is still changing, still cracking, still puffing out invisible gas that stains the ice black. The “spiders” that alarm the eye in these images are really a reminder that even a cold, thin atmosphere can keep a world in motion.

The official statement was published on the ESA Mars Express website.