Earth has quietly lost its only weather satellite around Venus. On September 18, 2025, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency carried out the final shutdown of the Venus Climate Orbiter Akatsuki, formally ending a mission that spent more than eight years watching the atmosphere of our nearest planetary neighbor.

Contact with the spacecraft had already been lost in late April 2024 after a problem in a lower-precision attitude control mode. Engineers tried for more than a year to reestablish communication, but the probe never answered again. Given the age of the craft and the fact that it had already worked far beyond its planned lifetime, mission managers decided it was time to close operations.

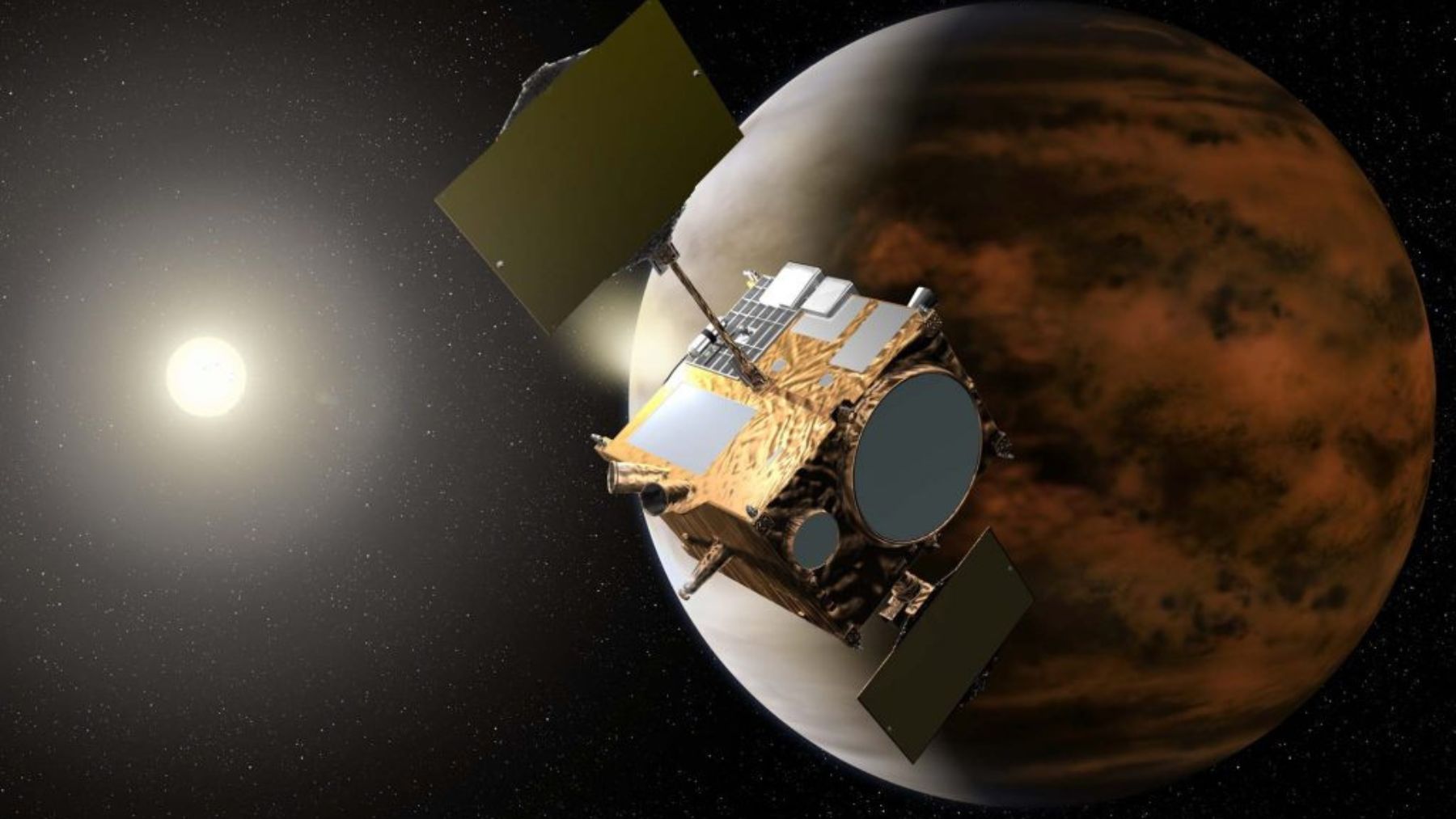

Akatsuki launch and Venus orbit

Akatsuki was launched from Tanegashima Space Center in May 2010 and finally slipped into orbit around Venus in December 2015, becoming Japan’s first successful planetary orbiter beyond Earth. Its path to Venus orbit was anything but straightforward. A first attempt to brake into orbit in 2010 failed when the main engine was damaged, leaving the probe circling the Sun instead. Five years later, engineers used smaller attitude thrusters to perform a second, delicate braking maneuver and rescued the mission.

Once in its elongated orbit, swinging between roughly 1,000 and 360,000 kilometers above Venus, Akatsuki settled into a routine that any weather satellite operator on Earth would recognize. The spacecraft carried five cameras that observed the planet from ultraviolet to long-wave infrared, along with an ultra-stable oscillator used for radio science.

Together they mapped clouds, probed temperature and pressure profiles, and searched for lightning and hints of volcanic activity in the thick Venusian atmosphere.

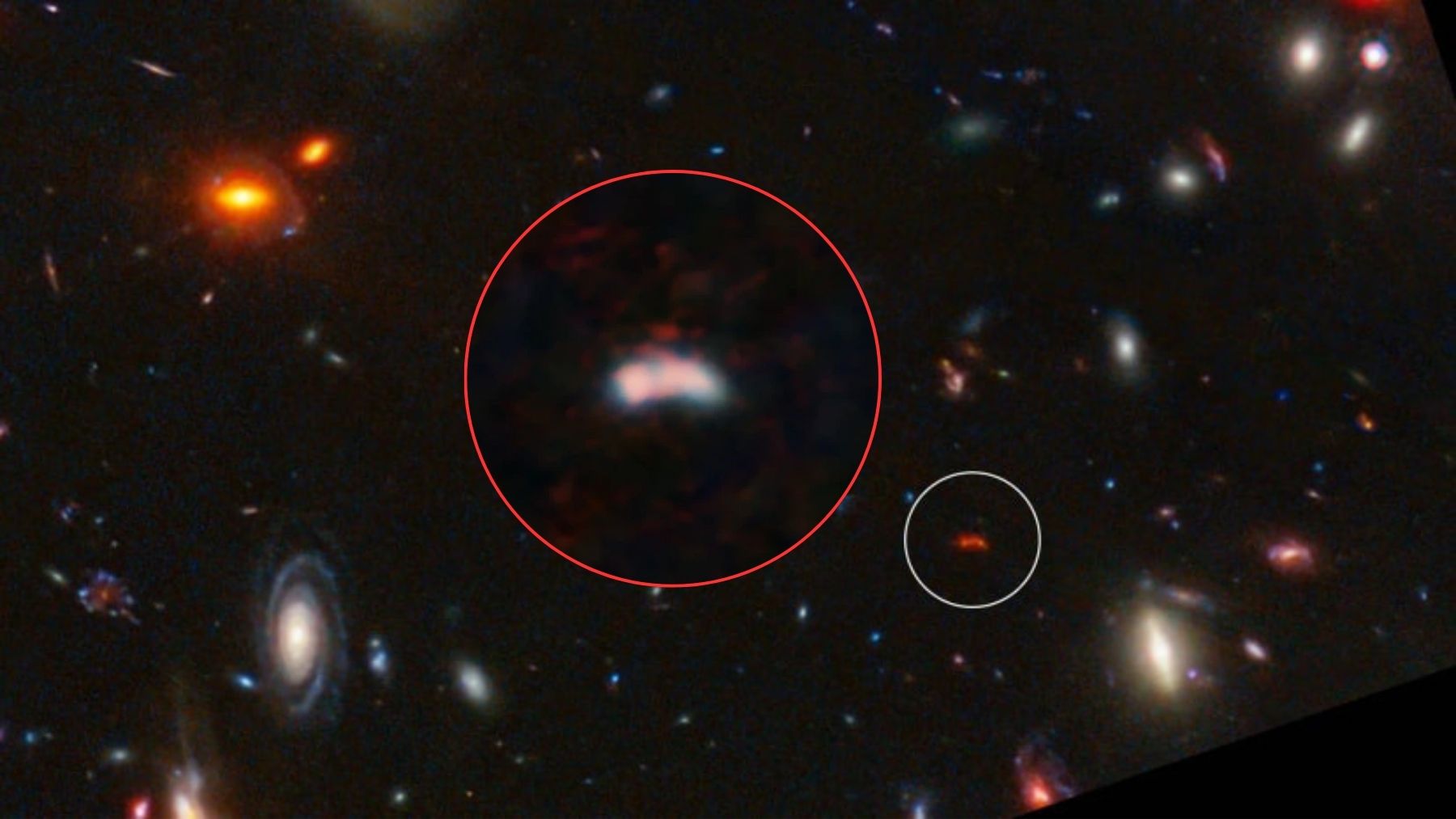

Akatsuki discoveries in Venus atmosphere

One of the mission’s headline discoveries came only hours after orbit insertion. Akatsuki spotted a gigantic, bow-shaped atmospheric wave, fixed over a mountainous region and stretching about 10,000 kilometers across the cloud tops. Researchers identified it as a stationary gravity wave, the largest such feature seen in the Solar System.

Later, the orbiter revealed a fast-moving equatorial jet in the lower and middle cloud layers, with wind speeds peaking near the planet’s equator. Those results helped refine the picture of Venusian super rotation, where the atmosphere whips around the planet in just a few Earth days while the solid surface crawls through a single rotation in about 243 Earth days.

Akatsuki also opened the door to a more Earth-like way of studying other planets. Using cloud motion tracked by its ultraviolet imager, scientists applied data assimilation techniques that are standard in modern weather forecasting centers. The combined models and observations produced the first objective three-dimensional analyses of thermal tides in Venus’ atmosphere, a key piece in understanding how super rotation is maintained.

Venus greenhouse effect and climate models

Why does all this matter for life back home, far from Venus’ scorching surface and crushing pressure? Venus is almost the same size as Earth but wrapped in an atmosphere that is about 96 percent carbon dioxide, nearly ninety times thicker than our own, with surface temperatures close to 460 degrees Celsius.

It is a natural laboratory for studying extreme greenhouse conditions and the limits of atmospheric stability.

When climate scientists test models, they do not only ask whether those models can reproduce today’s Earth. They also ask whether the same physics can handle very different worlds. Akatsuki’s long record of cloud motions, temperature structures, and atmospheric waves gives them an entire second data set for a planet that started out similar in size but ended up very different in climate.

Akatsuki mission legacy for planetary science

The scientific harvest will continue even though the spacecraft is silent. By JAXA’s own count, data from Akatsuki have already supported well over 170 peer reviewed journal papers, with more still in preparation. All of those results feed into open archives that researchers worldwide can mine for years, possibly decades, to come.

In its farewell note, JAXA stated that it wished to offer its deepest gratitude to all the organizations and individuals who supported Akatsuki throughout development and operations. For most of us, Venus will remain a bright point near sunset or sunrise, a familiar light above evening traffic or a quiet walk. Thanks to this small golden spacecraft, we now know that behind that soft glow lies a restless atmosphere, full of waves, jets, and storms that can teach us something about how any planet, including our own, can tip toward climate heaven or climate hell.

The official press release was published on the JAXA website.

Imagw credit: JAXA’s Institute of Space and Astronautical Science