High on a dry ridge above Peru’s Pisco Valley, more than 5,000 neat pits march up a hillside in tightly ordered rows. For decades, this so-called Band of Holes fed every possible theory, from water tanks to military trenches and even alien runways.

Now a new study argues that the feature known locally as Monte Sierpe was something more down to earth and, in many ways, more remarkable. It was probably a bustling barter market and a giant accounting device created by Indigenous societies long before paper money or spreadsheets existed.

Archaeology research using drone mapping

Archaeologists led by Jacob Bongers at the University of Sydney combined high resolution drone mapping with microscopic analysis of ancient plant remains trapped in the pits. They found that the band stretches for about 1.5 kilometers along a narrow ridge and contains roughly 5,200 holes, each about one to two meters wide and up to one meter deep, grouped into compact sections separated by walkways.

The layout is not random. When the team counted hole by hole, they saw repeating numerical patterns inside each block, similar to how an accountant might group entries on a ledger.

Inca khipu and Indigenous accounting

Those patterns echo something familiar from the Inca world. In the same valley, a complex khipu, a knotted cord device used for record keeping, shows its pendant strings organized into groups of 10 to 12 with intricate numerical relationships.

The researchers note that the segmentation of Monte Sierpe mirrors the way numbers are bundled in that khipu, which suggests a shared logic of counting and control. One author describes the ridge as a possible “landscape khipu,” a physical extension of Indigenous accounting knowledge into the terrain itself.

Pollen evidence and ancient trade goods

The plant evidence tells an equally important part of the story. From 21 sediment samples inside the holes, the team recovered pollen from maize, cotton, chili peppers and other useful crops, along with bulrush and native willow, plants long used in the region for baskets and mats.

Many of these species shed little wind-blown pollen, and Monte Sierpe sits on a barren slope with no irrigation, so their presence points strongly to human transport rather than chance. One possibility raised by the authors is that people periodically lined the holes with plant fibers and placed baskets of goods inside them during trading events.

Pre-Inca open-air market and exchange

If that is right, Monte Sierpe starts to look like a pre-Inca open-air market designed for a world without coins. Instead of stalls and price tags, quantities may have been tracked visually. Imagine walking along the ridge and seeing sections where every pit is filled with corn or cotton.

Even without written numbers, anyone could gauge surplus, scarcity and fair exchange at a glance. As Bongers puts it, the holes can be seen as a kind of “social technology” that helped people come together and organize what they produced.

Chincha Kingdom trade networks and roads

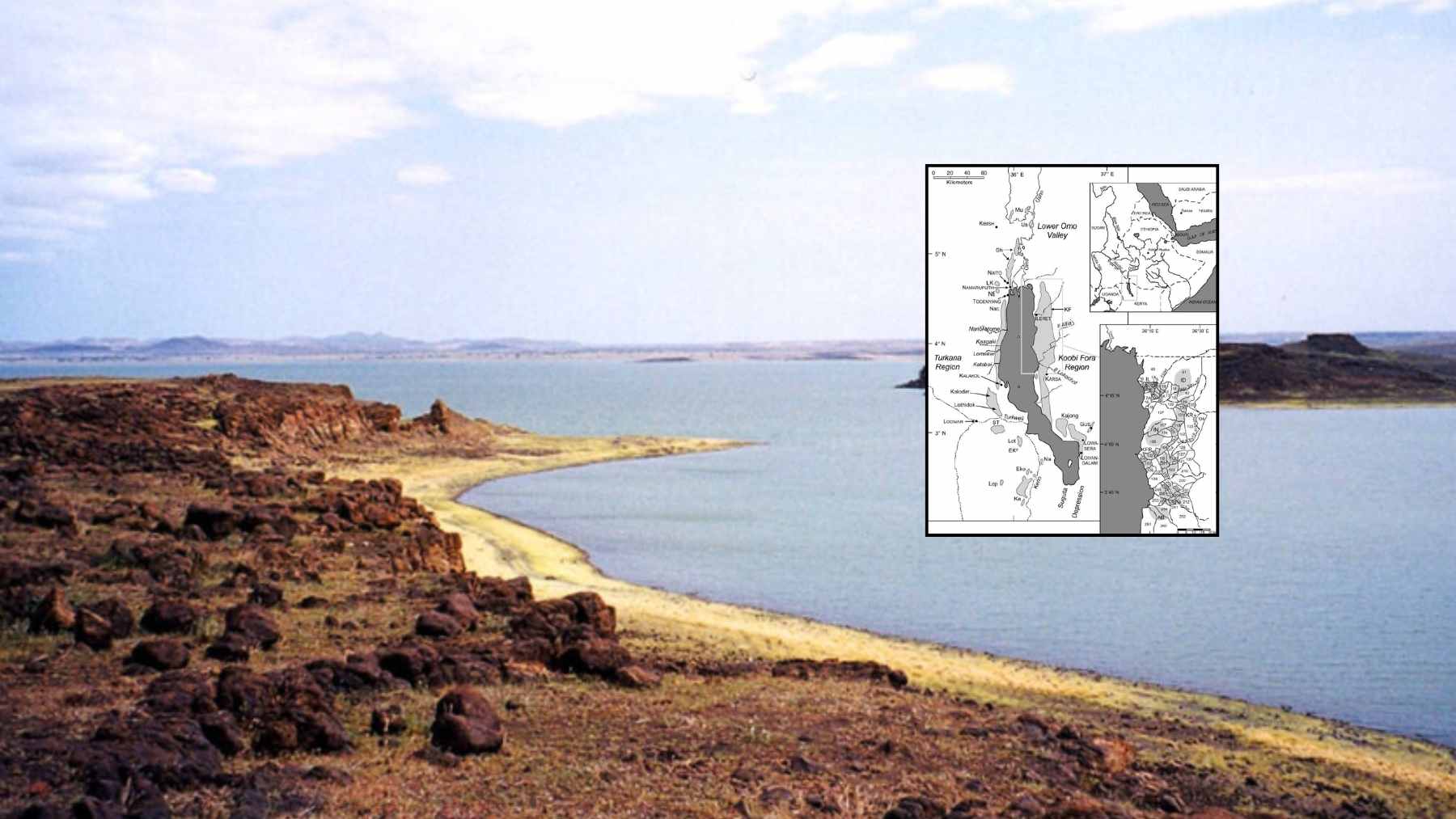

Location strengthens this interpretation. The ridge lies in the chaupiyunga, a narrow ecological transition between the coastal desert plain and the Andean valleys. It sits at a crossroads of major pre-Hispanic roads that linked the Chincha and Pisco valleys and connected coastal towns to highland communities and mineral sources.

For the Chincha Kingdom, which had a population of more than 100,000 people during the Late Intermediate Period, such a node would have been ideal for periodic fairs where farmers, fisherfolk, llama caravans and seafaring merchants met to swap food, textiles and other essentials.

Inca Empire administration and Inkawasi

Later, when the Inca Empire absorbed Chincha territory, the same infrastructure could be folded into state administration. The authors point to Inca storehouses at Inkawasi, farther north, where grid-like floor markings and khipus appear to have been used together to manage agricultural stocks.

At Monte Sierpe, they argue, each section of holes may have been tied to a specific community that owed tribute in maize or other goods. Filling a defined block of pits would then stand in for a tax payment, a highly visual way for imperial officials to track who had delivered what.

Alternative theories and site climate

Crucially, the new data also weaken other long-standing ideas. The team found no associated fortifications, weapons, human burials or mineral ores, which makes defensive walls, cemeteries or mining spoils unlikely.

Rainfall at the site is close to zero, and groundwater is not accessible on the slope, so arguments that the holes captured water for crops fit poorly with both the climate and the plant remains discovered. The nearby Pisco River already offers a more reliable water source for farming on the valley floor.

Sustainability and resource use lessons

What does an ancient hillside ledger have to do with the present day conversation on sustainability and resource use? Quite a lot. Monte Sierpe shows that Indigenous societies in the Andes invested serious labor in tools that helped them coordinate exchange across ecological zones, share goods and keep inequality in check without cash or written numerals. The monument hints at a system where accounting was embedded in the landscape itself, visible to anyone willing to climb the ridge. In an era when modern supply chains feel abstract and distant from daily life, that very visibility is striking.

The researchers stress that questions remain. Radiocarbon dates are still sparse, goods themselves did not survive in the pits, and other functions such as symbolic display cannot be fully ruled out. Even so, the combination of patterned layout, plant traces and strategic geography now offers the strongest case yet that this desert band once thrummed with trade and careful counting.

At the end of the day, Monte Sierpe reminds us that managing food, fiber and water across harsh environments is not a new problem. Long before climate dashboards and carbon budgets, people on this Peruvian hillside were already tracking who brought what from which ecosystem. Their “spreadsheet in stone” still runs up the ridge, a quiet record of how culture, commerce and landscape once fit together.

The study was published on the site of the journal Antiquity.