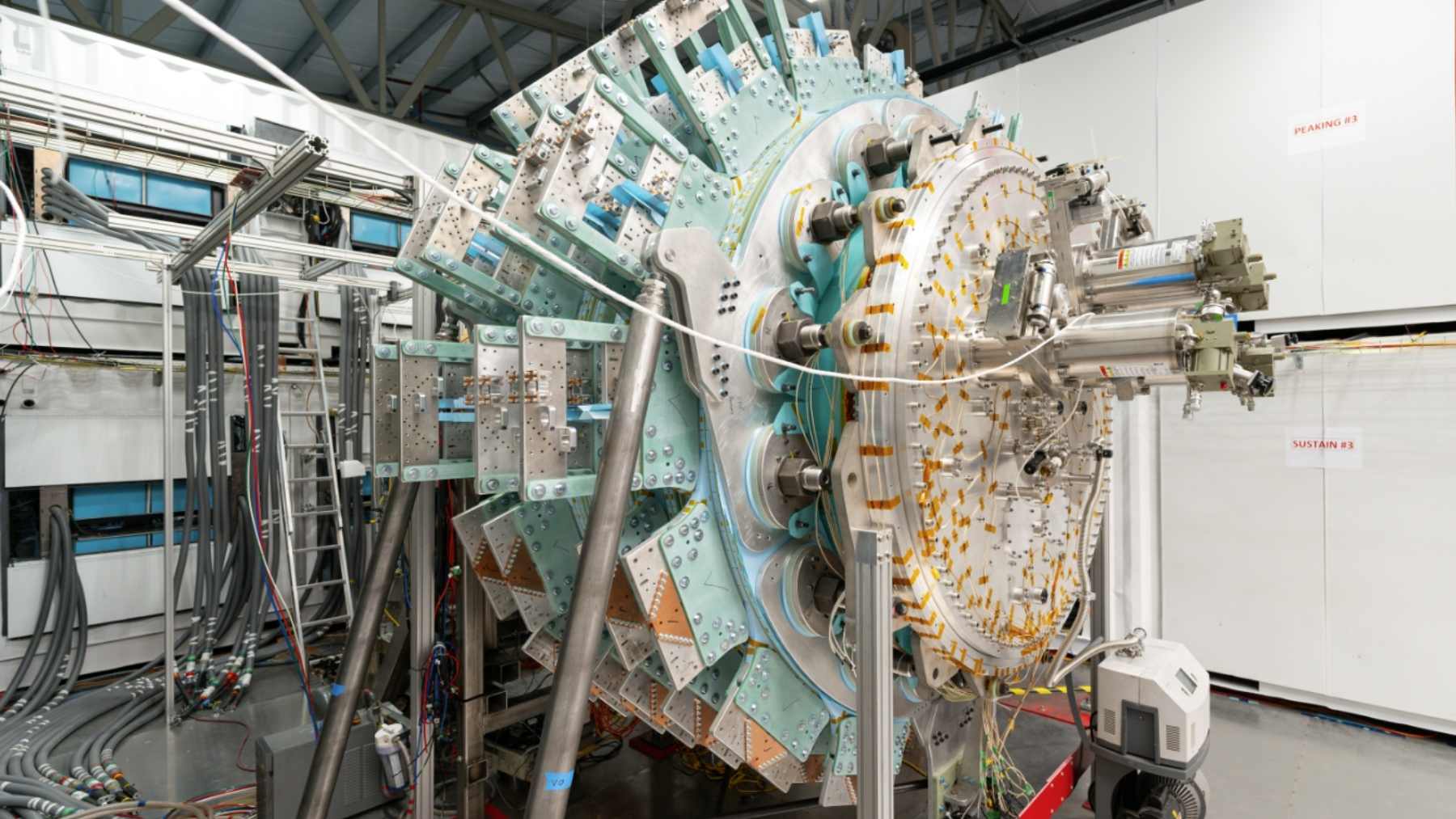

Imagine debunking a 100-year-old myth that essentially solves the future of wind power… that’s what a Penn State University aerospace engineering master’s student did, unintentionally, when she solved a mathematical puzzle as part of her senior thesis in the Schreyer Honors College. What was once just a piece of work for academic recognition now appears to have the potential to impact wind turbine design around the world.

The calculation that showed gaps in the 100-year model

It all started with the maximum efficiency model developed by Hermann Glauert, a British aerodynamicist. Just to give you an idea, this formula has been established since the 20th century that is, no one had refuted it, at least until now. What does this model do? Well, it defines the power coefficient, which, translated into less technical terms, is a measure of how much wind power a turbine can transform into electricity.

This model was used for many, many years, without anyone refuting it. It was applied mainly to identify the ideal air flow conditions that would maximize energy generation efficiency. However, with the advancement of engineering technologies and the high demand for clean energy, questions arose: Is the model prepared for the real demands of current projects? That’s when Divya Tyagi, a master’s student in aerospace engineering at Penn State University, saw an opportunity to put the model to the test and so, using the calculus of variations, restructured the model, maintaining its conceptual basis, but resolving gaps that had been ignored for 100 years.

Which 00-year-old myth was debunked?

What happened was that Hermann Glauert ended up not considering the fundamental forces that act on the blade of a turbine. What does this mean? In wind energy, we have:

- The downwind thrust.

- The root bending moment.

Both are essential forces for the structural performance and safety of modern turbines.

“If you have your arms outstretched and someone presses on your palm, you have to resist that movement. We call this the downwind buoyancy force and the root bending moment, and wind turbines have to withstand that too. You have to understand the size of the total load, which Glauert didn’t do.”, Said Sven Schmitz, a Penn State professor and Tyagi’s advisor

Now, this new model proposed by Tyagi ends up solving this problem in a simple and elegant way, because by incorporating these additional forces, she created a formula that is more applicable to the current context. And the best of all is: with this new formula, the model is not complicated, but simpler and more applicable for engineers. It seems that wind power will become even easier to implement (an example of this is this wind turbine that you can put in your house and generate 600W).

What is the real impact of this discovery on wind power?

With this discovery by the student, Divya Tyagi, we will have a 1% increase in the power coefficient of a turbine, which, even though it may seem small, represents a huge gain in our energy production. In a practical example, this increase could be enough to supply an entire neighborhood…

And of course, this impact will only multiply, because when we apply this improvement to hundreds or thousands of turbines, we will have real gains in energy efficiency, cost reduction, and economic viability for the expansion of wind farms. The result that this will have on wind power is impressive. If wind power is already gaining more and more ground, as in this new silent wind turbine that offers 1500 kWh for free at home, imagine what we can achieve with this correction in efficiency