For decades, the SS United States sat quietly along the Delaware River in Philadelphia, a rusting reminder of the age of glamorous ocean crossings. Now this nearly 1,000-foot vessel is on a very different kind of voyage, headed toward a new role on the seafloor of the Gulf of Mexico as the world’s largest artificial reef.

County officials in northwest Florida plan to sink the ship in early 2026 about 22 nautical miles southwest of Destin and roughly 32 nautical miles southeast of Pensacola. Once in place, the hull will rest at a depth of around 180 feet, with the upper decks only about 60 feet below the surface, shallow enough for many recreational divers to visit.

For Susan Gibbs, president of the SS United States Conservancy and granddaughter of the ship’s designer, the moment is emotional. The vessel, she said, will always symbolize national strength, innovation and resilience, even if its next chapter unfolds underwater.

A speed record that still stands

When the SS United States entered service in 1952, it shattered the transatlantic speed record on its maiden voyage, crossing from New York to Europe at an average of about 36 knots. The ship still holds the Blue Riband for the fastest westbound crossing by an ocean liner, a record that no passenger ship has beaten.

The vessel was designed with more than luxury suites and celebrity passengers in mind. Its structure and engines were built so it could also serve as a high-speed troop carrier during wartime, moving thousands of soldiers across the ocean much faster than earlier liners.

Then air travel took over. By 1969 the ship was out of service and eventually wound up docked in Philadelphia, cycling through a series of private owners and unrealized plans for conversion into a hotel or museum.

A long-running rent dispute with the pier operator culminated in a federal order to move the ship and, eventually, its sale to Florida’s Okaloosa County for about one million dollars.

Turning steel into habitat

Right now the SS United States is in Mobile, Alabama, where crews are spending many months stripping out hazardous materials such as chemicals, wiring, plastics, glass and remaining asbestos. The idea is to leave behind a clean steel shell that can safely host corals, sponges, fish and other marine life.

Once remediation is complete, tugboats will tow the empty hull to a permitted site in the Gulf. Planning documents show the ship will settle at roughly 180 feet to the bottom, with its upper decks near 55 to 60 feet, creating a towering vertical structure in an area that has relatively little natural reef.

Florida already runs one of the most active artificial reef programs in the United States, with more than four thousand planned public reefs off its coasts. Okaloosa County alone has deployed over twenty large vessels and is home to more than five hundred artificial reef sites in the wider region.

In practical terms, that means charter boats lined with divers and anglers heading out from Destin and Pensacola will have a new headline destination on the GPS. For local businesses, the project is part conservation tool, part economic engine.

County officials estimate total costs of around ten million dollars, supported in part by tourism authorities in Pensacola and by Coastal Conservation Association Florida.

Do artificial reefs really help the ocean?

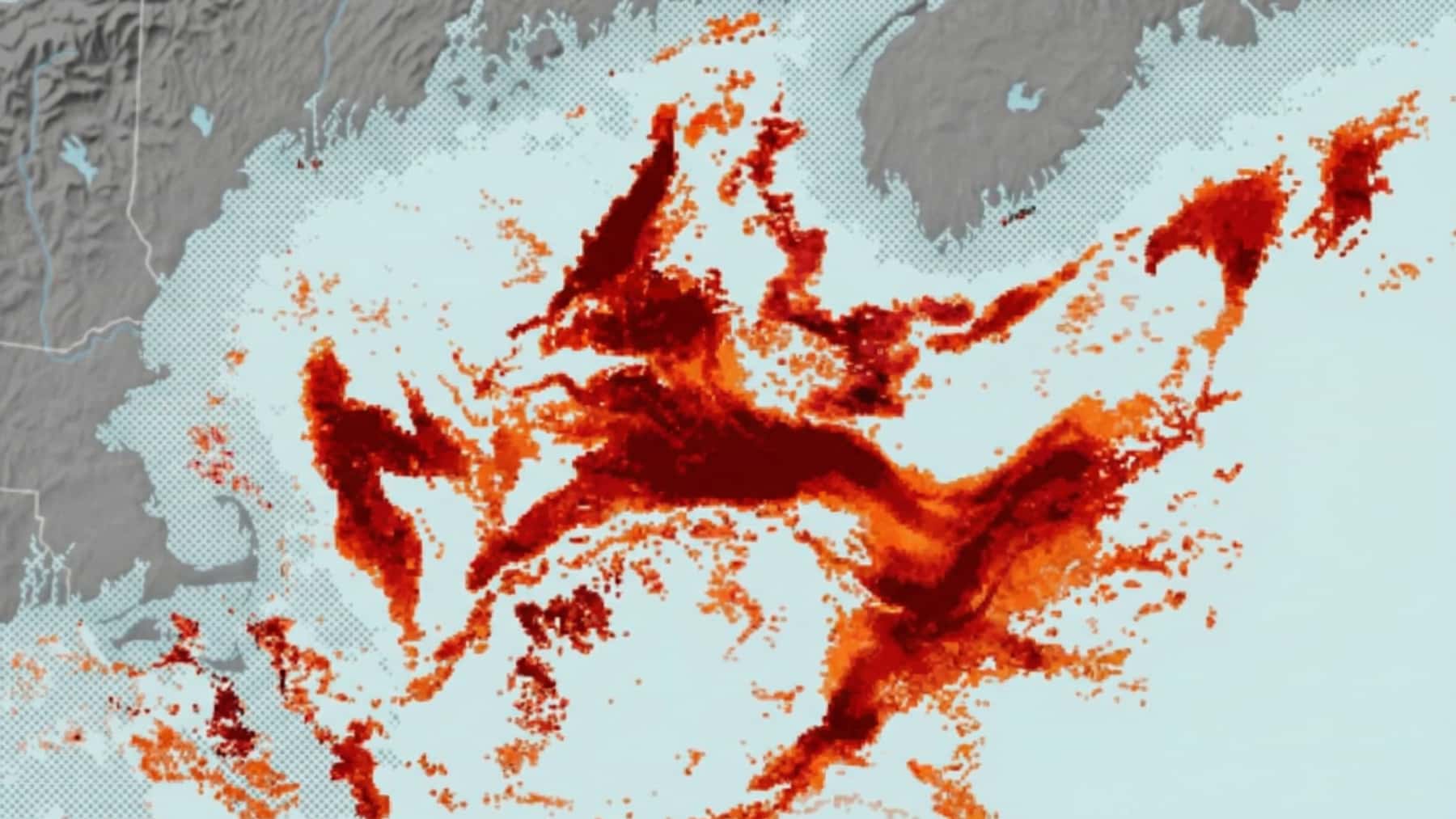

Artificial reefs are human-made structures placed on the seafloor to mimic some functions of natural reefs. They provide hard surfaces and nooks where algae, corals and invertebrates can settle, which in turn attract fish and other marine life.

Studies in the Gulf of Mexico and elsewhere suggest that shipwrecks and other artificial reefs can become busy underwater neighborhoods, sometimes with fish communities that rival nearby natural reefs.

The story is not completely straightforward though. Researchers with NOAA and university teams have warned that artificial reefs can concentrate fish in one place, making them easier to catch and potentially speeding up overfishing if regulations are weak. Others note that metal structures may help non-native species spread by giving them new footholds.

That mix of promise and risk is one reason large reefing projects like the USS Oriskany aircraft carrier and now the SS United States are preceded by detailed environmental reviews and long-term monitoring plans.

The Oriskany, which was sunk off Pensacola in 2006, is currently considered the world’s largest artificial reef. The SS United States, at roughly 990 feet, is expected to overtake that title.

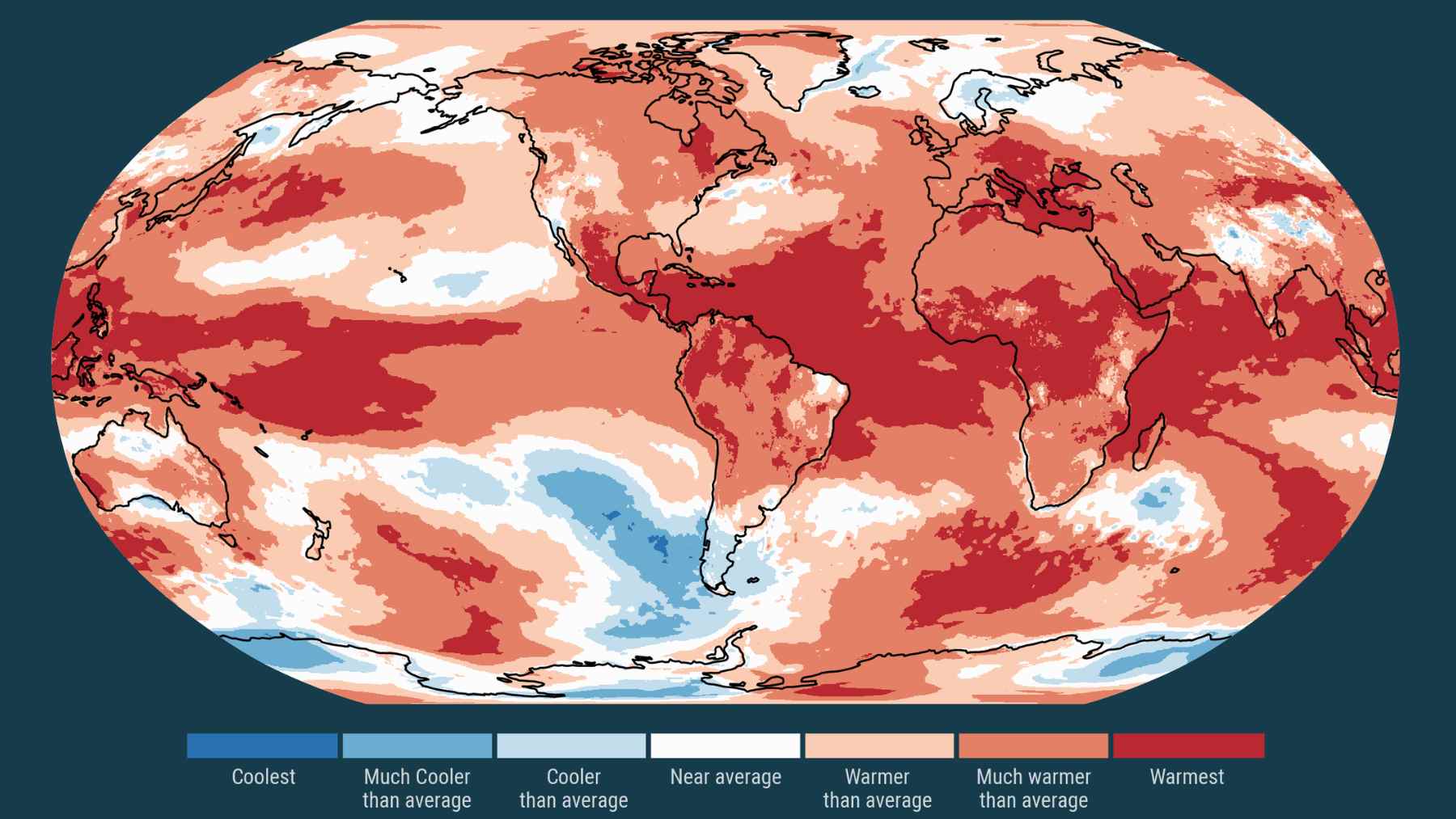

Heritage, memory and a warming sea

Not everyone is ready to watch the ship disappear beneath the waves. Preservation groups in New York and elsewhere pushed for a last-minute rescue and argued that once the hull is on the seabed, the chance to restore it as a museum ship is gone forever.

The New York City Council even passed a resolution in December urging federal authorities to stop the sinking, although a federal complaint from a citizens’ coalition was dismissed earlier in the year.

Supporters of the reef project counter that the alternative is not a floating museum but likely scrapping. They argue that reefing the vessel protects at least part of its structure and allows its story to live on in a different form.

The plan includes a land-based museum in Destin Fort Walton Beach, where visitors will be able to see salvaged features such as funnels and masts along with archival material from the ship’s heyday.

At the end of the day, the SS United States is becoming a test case for how we treat big industrial relics in a century of climate stress and ocean change.

Instead of sending the ship to a breaker’s yard, Okaloosa County is betting that a carefully cleaned hull on the Gulf floor can support marine life, attract visitors and keep a piece of maritime history in the public eye.

Whether that bet pays off for the ecosystem will depend on long term science and careful fisheries management, not just the splashy moment when the hull finally slips below the surface.

The official project information was published on the Okaloosa County SS United States FAQs page.