If you have ever walked away from a hot pan for “just a second” and come back to a kitchen that still feels warm, you already get the basic idea here. Heat doesn’t always leave on your schedule. Earth’s oceans have been doing a much larger version of that, soaking up most of the extra heat trapped by greenhouse gases.

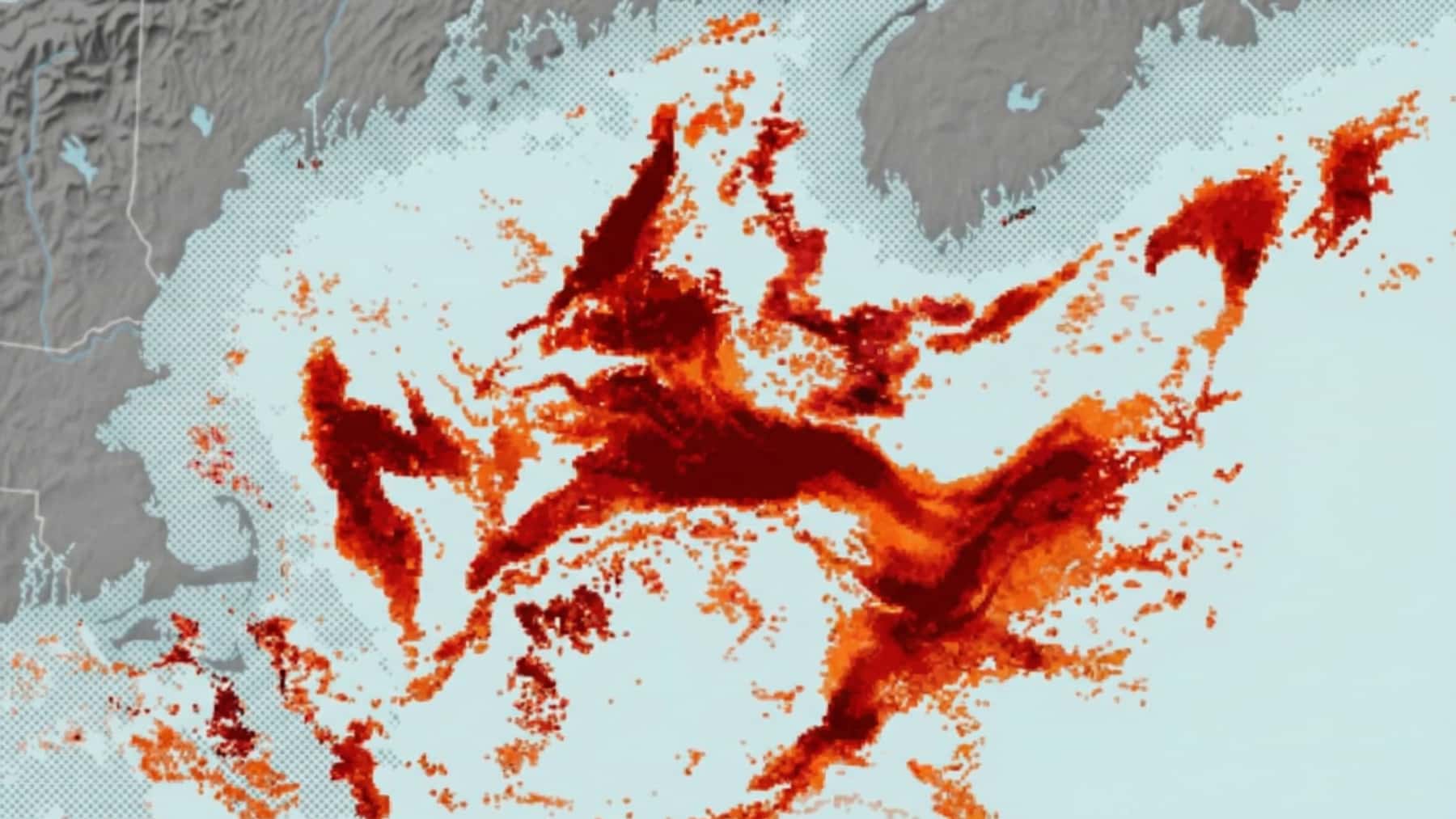

Now, a new modeling study suggests the Southern Ocean around Antarctica could eventually give some of that heat back, even in a future where humans cut emissions and global temperatures start to fall. The surprise is the timing: the warming “kick” shows up after centuries of cooling in the model, not right away. And once it starts, it can keep warming the atmosphere for more than a century.

Why could the Southern Ocean warm the planet again after emissions drop?

The key point is that the ocean is not just a surface layer that reacts instantly. It is a huge heat reservoir, and official sources regularly note it has absorbed around 90% of the excess heat associated with global warming. That buffering is helpful, but it also means the ocean can “hold onto” heat for a long time.

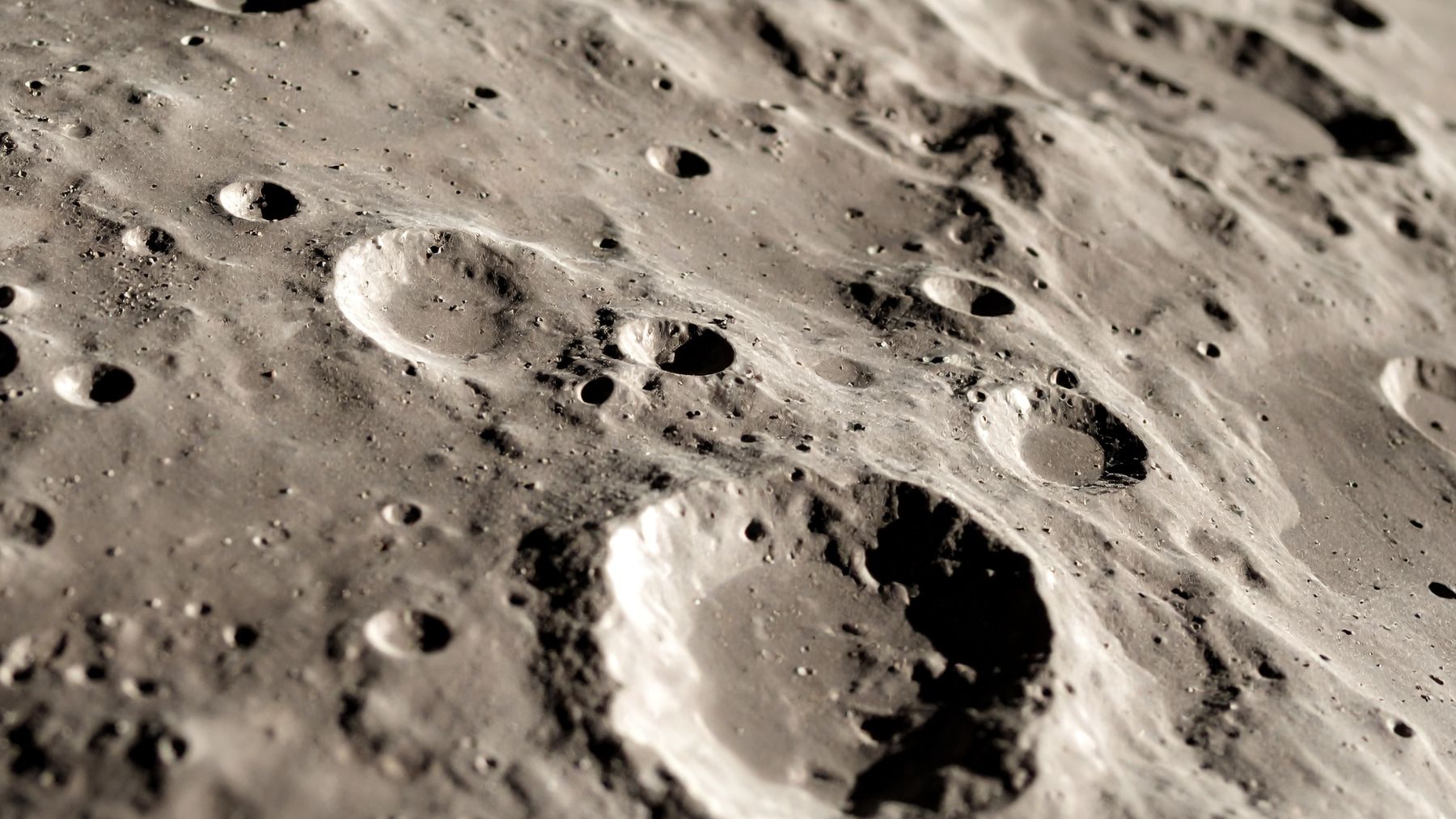

GEOMAR researchers describe the Southern Ocean as a kind of “exhaust valve” for the global ocean system: a place where heat stored deep below can eventually escape back to the atmosphere.

In their simulations, that release can come back as a renewed warming phase after a long cooling period, with temperatures rising at rates comparable to those seen during the past 150 years.

How did scientists model this century-plus warming pulse?

The GEOMAR team used an “intermediate-complexity Earth system model,” meaning a simplified climate model designed to run very long simulations (centuries to millennia), even if it is less detailed than higher-resolution models. In this case, GEOMAR notes they used UVic v. 2.9, developed at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada.

In the idealized scenario they tested, atmospheric CO2 rises by 1% per year until it doubles at year 70, then declines at -0.1% per year, representing sustained “net-negative emissions” (removing more CO2 from the air than humanity emits).

After about 400 years of net-negative conditions and gradual cooling, the model shows an abrupt reemergence of heat that raises global average surface temperature by several tenths of a degree and lasts more than a century.

What physically triggers the heat release in the model?

The EGU abstract points to deep convection, which is basically vigorous vertical mixing in the ocean: cold, dense surface water sinks and churns the water column, allowing warmer deep water to reach the surface and exchange heat with the atmosphere.

In this modeling work, the stored heat is concentrated at depth in the Southern Ocean and later “re-emerges” through this process.

GEOMAR stresses that the scenario is idealized and the model has limits. For example, their release notes the model’s spatial resolution is limited and it does not include certain processes such as ice-sheet melt. In plain English; this is not a calendar prediction, it is a warning that ocean heat can behave in lags and jumps over very long time frames.

Does a heat rebound also mean a CO2 rebound?

Not necessarily, and that is one of the study’s headline findings. The EGU abstract says the modeled heat pulse is “largely devoid of CO2,” and attributes that to two things: circulation changes affect heat more than carbon, and seawater chemistry can “mute” CO2 loss.

GEOMAR similarly reports that the model did not simulate a comparable CO2 release, suggesting seawater chemistry retains a large share of dissolved carbon. That matters because it points to a warming pulse that is driven by stored ocean heat, not by a sudden new spike in atmospheric CO2.

What can you do with this info if climate plans affect your life and wallet?

First, don’t read this as “cutting emissions is pointless.” Official sources underline the opposite: stopping greenhouse gas emissions prevents even more heat from piling up in the ocean, and GEOMAR calls cutting current CO2 emissions to net zero “the most important step right now.” In other words, the cheapest heat to manage is the heat you never trap in the first place.

Second, it’s a reminder that climate policy and long-term planning (infrastructure, insurance, coastal preparation, and energy systems) cannot treat the year 2100 like a finish line. Here are practical steps grounded in what the official sources emphasize:

- Check whether your city or state climate plan includes both near-term emission cuts and long-term monitoring, especially for ocean-driven risks.

- When you see “net-negative emissions,” remember it means CO2 removal exceeds emissions, and treat it as a complement to cutting pollution, not a magic refund for burning fossil fuels.

- Follow updates from major public science agencies (NASA, NOAA, IPCC, UN) on ocean heat and carbon uptake, since these numbers shape timelines and risk assessments.

- Support (as a voter, ratepayer, or stakeholder) sustained ocean observation and research, because GEOMAR notes the Southern Ocean is harder to study and has been observed less than regions like the North Atlantic.

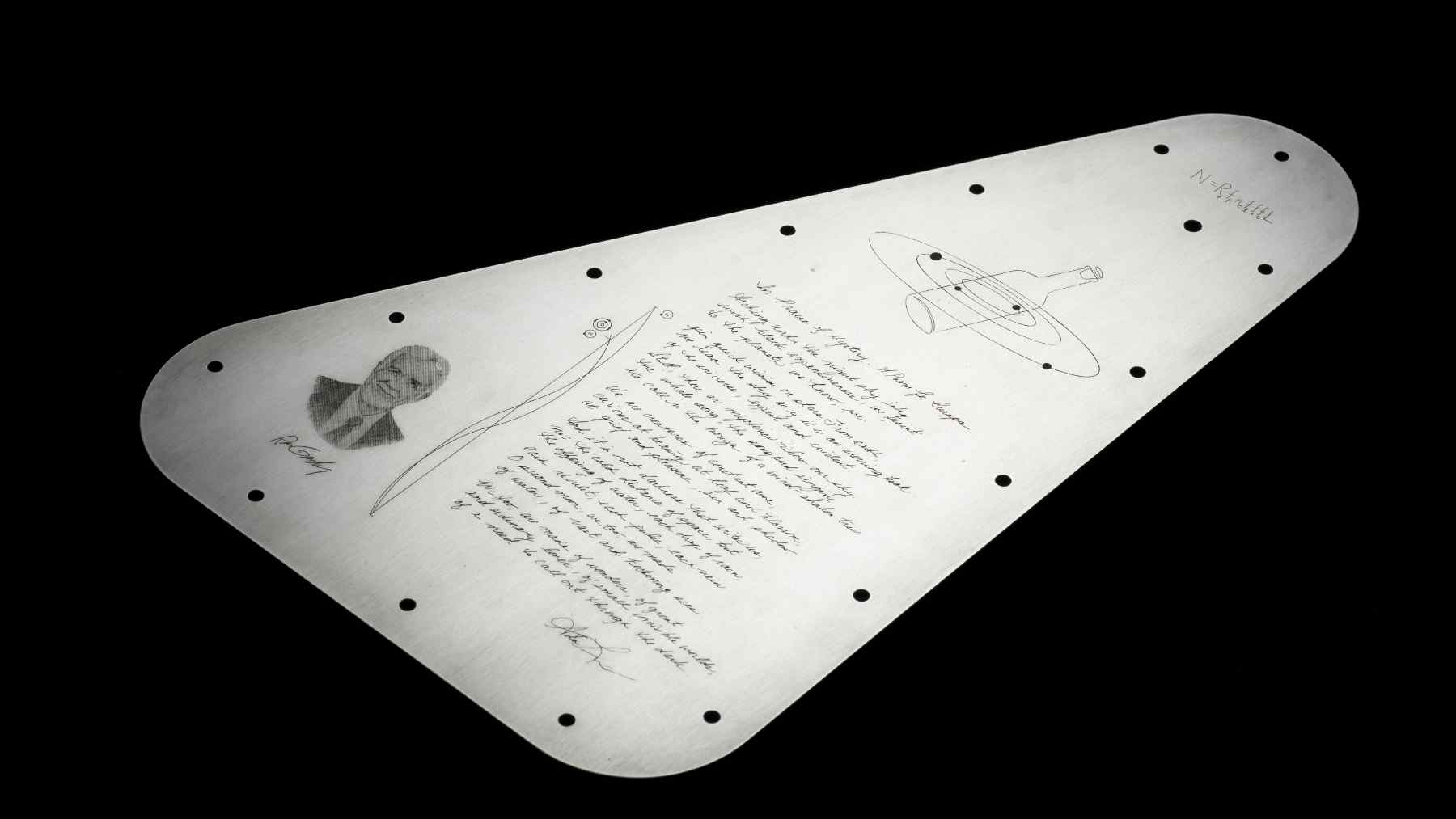

The bottom line is frustratingly ordinary: the ocean keeps receipts. Even with future CO2 removal, the study suggests deep-ocean heat could still shape temperatures for generations, which is exactly why cutting emissions sooner reduces the size of the bill later.