Winter’s most intense meteor shower reaches its brief peak overnight on January 3 to 4, giving skywatchers a chance to see bright “shooting stars” streak past a dazzling full Wolf supermoon. The Quadrantid meteor shower is famous for sharp bursts of activity and eye catching fireballs, even when the sky is washed in moonlight.

On paper, this shower can produce well over sixty meteors per hour under perfect dark skies, and in rare cases close to two hundred. In practice, experts at the American Meteor Society and NASA say the full moon will knock that down to roughly ten visible meteors each hour for most observers, although a few brighter streaks could still easily grab your attention in the backyard.

When and where to look tonight

The Quadrantids are active from late December into mid January, but the real action clusters into a window of only a few hours. For the 2026 display, calculations collected by meteor observer Robert Lunsford at the American Meteor Society put the peak sometime between late evening and around midnight Universal Time on the night of January 3 to 4, a timetable that favors Asia, with Europe close behind and North America seeing lower rates toward dawn.

If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, your best bet is to head outside after local midnight and watch until the first light of morning. The meteors seem to fan out from a spot in the constellation Bootes, near the old, now unused constellation Quadrans Muralis, close to the end of the Big Dipper’s handle. In real life you do not need to “find” that point with an app; simply choose a spot with a wide view of the northern and northeastern sky and look up.

Why this strong shower can still feel subtle

At first glance, the Quadrantids should be a showstopper. NASA notes that during the brief maximum, the shower can theoretically produce sixty to two hundred meteors per hour for an ideal observer under a perfectly dark sky high in the Northern Hemisphere.

Reality is messier. The American Meteor Society points out that the stream of debris is very thin, and Earth cuts through it almost straight on, so strong activity lasts only about six hours before rates drop sharply. Add in early January cloud cover plus a bright supermoon and those impressive numbers quickly shrink, which is why forecasts for this year range from ten to twenty meteors per hour from the best locations in Asia and closer to ten or fewer in Europe and North America.

What makes the Quadrantids different

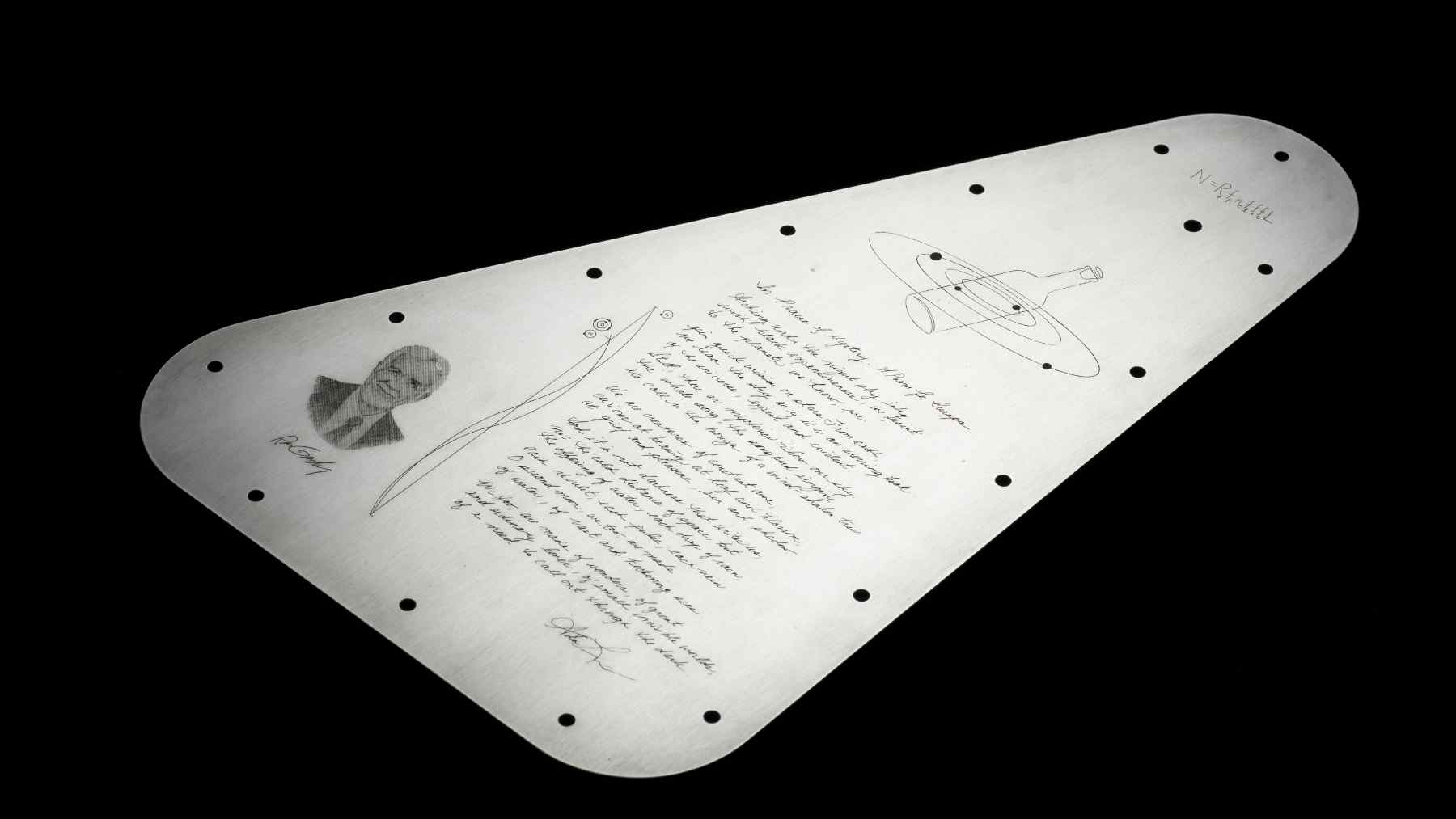

Most famous meteor showers come from icy comets, but the Quadrantids are tied to a rocky body known as asteroid 2003 EH1. NASA’s Quadrantids overview describes this object as a small near Earth asteroid about two miles wide that orbits the Sun roughly every five and a half years and may be a “dead comet” or “rock comet” whose ice has long since evaporated.

Dutch American astronomer Peter Jenniskens, now a researcher with NASA’s Ames Research Center, was the first to show that 2003 EH1 is the source of the Quadrantid meteors. Tiny grains shed from this body slam into our atmosphere at around twenty five miles per second, heating the air and vaporizing in a split second streak of light. Larger fragments create the bright fireballs that give this shower its reputation and can briefly rival the brightest planets, even in a sky flooded by the Wolf Moon.

Tips to catch meteors under a full supermoon

A full supermoon is not ideal for meteor watching, but it does not have to ruin the night. Try to put the Moon behind a building, hill, or tree line so you are not staring straight into the glare. Give your eyes at least twenty minutes away from phone screens or porch lights and dress for the kind of cold that makes you dream about hot chocolate and lower heating bills.

You do not need a telescope or binoculars. In fact, they make things harder because meteors can appear anywhere overhead. Lie back on a blanket or reclining chair with your feet roughly toward the northeast and keep your gaze drifting across as much sky as you can. You may only see a handful of meteors during an hour, but a single bright fireball that lights up the yard for a heartbeat is often what people remember years later.

A busy year of sky shows ahead

Tonight’s Wolf Moon is the first of three supermoons expected in 2026, according to lunar calendars compiled by professional observatories and skywatching guides. Later in the month, Jupiter reaches opposition on January 10, when Earth moves directly between the giant planet and the Sun, turning Jupiter into a brilliant, all night beacon worth a look through any small telescope.

The rest of the year is packed as well. A total lunar eclipse on the night of March 2 to 3 will turn the Moon a deep red for observers across large parts of North America and the Asia Pacific region, and a dramatic total solar eclipse will sweep over Greenland, Iceland, and northern Spain on August 12. By the time a Christmas Eve supermoon rises on December 24, many skywatchers may have stories of meteor showers, eclipses, and bright planets that all began with stepping outside on this cold January night.

If you have ever thought about getting into stargazing, the Quadrantids offer a low tech way to start, no apps or fancy gear required. Just your eyes, some patience, and a willingness to look up for a while.

The official statement was published on American Meteor Society.

Image credits: NASA/SETI/P. Jenniskens.