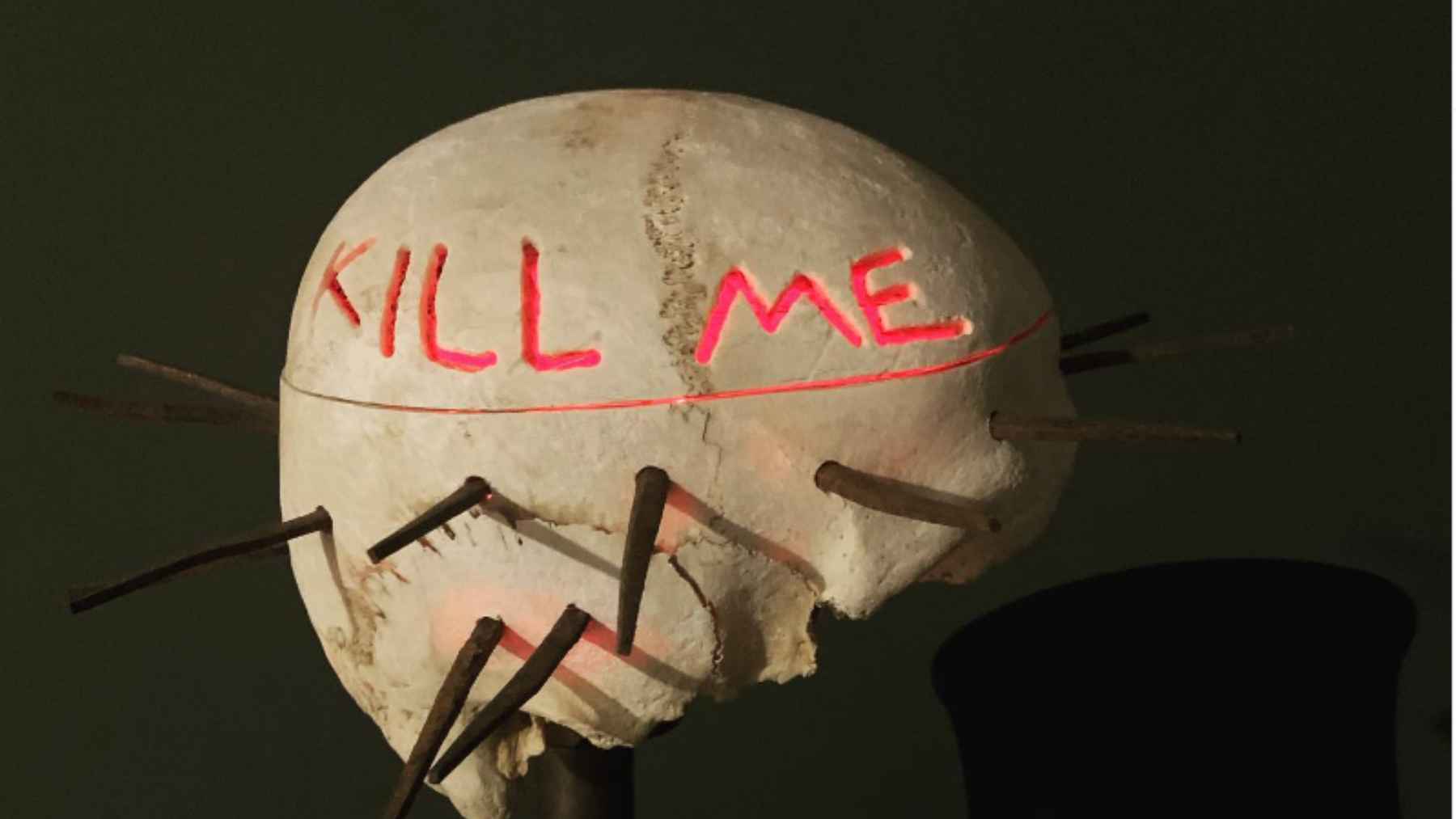

A human skull on a bookshelf might look like a movie prop. Today the same image pops up in TikTok videos and aesthetic Instagram shots, next to houseplants and stacks of books. Behind those carefully staged scenes sits a fast-growing market in real human bones that is now worrying specialists who work with the dead every day.

Michelle Spear, a professor of anatomy at the University of Bristol, has traced how skulls, long bones and even modified human remains are sold through mainstream online marketplaces and social media.

What once moved quietly between specialist collectors has become a global trade powered by hashtags and late-night impulse buys. The result is that human remains are edging closer to ordinary consumer culture.

Skulls for sale on social media

The buyers come from many worlds. Traditional collectors of curiosities, ritual practitioners and some contemporary artists all use human bones as raw material. A newer wave is more casual. Fans of the aesthetic known as “dark academia” mix gothic literature, candlelit desks and vintage clothing with a scholarly mood, and real skulls and skeletons are starting to appear inside that look.

On feeds tagged “SkullDecor” or “OdditiesTok”, skulls sit beside antique books or glow under string lights like designer objects.

At first glance, it can feel like a harmless style choice, not so different from an old globe or a vintage lamp. Yet the person behind those bones disappears, reduced to a prop on a shelf.

Researchers warn that this trend normalizes private ownership of human remains and blurs the line between teaching specimens and people who once had names, families and communities.

A legal patchwork that invites abuse

The law has not kept pace with this shift. In the United Kingdom, the Human Tissue Act 2004 regulates how donated bodies can be used for teaching and research, but it only applies to remains that are less than one hundred years old. Anything older usually falls outside that system.

That simple age cutoff creates a convenient gray area. A seller can describe a skull as Victorian and imply that it is safely more than a century old, even when the real story is unclear. Buyers rarely demand documentation and platforms often do not require it.

In the United States, federal law protects Native American remains, but state rules differ and enforcement online is uneven. Because sales cross borders so easily, a skull listed in one country can be shipped to another with very little scrutiny.

A colonial supply chain in the background

Behind many of these objects lies a long and uncomfortable history. Nineteenth century reforms such as the Anatomy Act of 1832 were meant to stop grave robbing in Britain by allowing unclaimed bodies from hospitals, prisons and workhouses to be used for medical teaching. Demand still outstripped supply, so by the late nineteenth century Britain began importing bones.

India became the main exporter. In the 1980s, estimates suggest that about 60,000 complete skeletons left the country in a single year. Many came from poor families who could not afford cremation or burial, while others were taken from cemeteries without consent.

The trade rested on colonial power structures and continued long after Indian independence in 1947, until a scandal in 1985 exposed exports of around 1,500 child skeletons. India banned the trade, and China later became the leading supplier before prohibiting exports in 2008.

Those bans did not make existing skeletons disappear. Many remained in university teaching collections or private cabinets. Today some of these old specimens are resurfacing on open markets, even though the people they once belonged to were often treated as expendable in both life and death.

Why respect for the dead still matters

At the heart of this debate sits a simple question. Should human remains be commodities at all? Spear argues that “human remains are not ornaments or lifestyle accessories” and that they are better understood as physical traces of individual lives.

The market thrives in part because laws leave room for loopholes and because online platforms benefit from traffic even when listings sit uneasily with their own policies. Ordinary consumers play a role too.

Every time someone clicks buy on a skull or shares a stylish video without asking where the bones came from, they help turn a person into a product.

There are other ways to explore anatomy, history and our long fascination with death. Museums can display documented specimens and explain their origins. Ritual objects and decor can be made from sustainable materials instead of remains taken from distant cemeteries.

For the most part, this is less a technical legal issue than a question of dignity. Human remains, whether ancient or recent, carry stories of identity, community and loss.

Treating them as collectibles does not only diminish those who died. It also says something deeply unsettling about the values of the living.