If you have ever dropped your phone between the car seat and the center console, you know the feeling: one second it’s in your hand, the next it’s in another dimension.

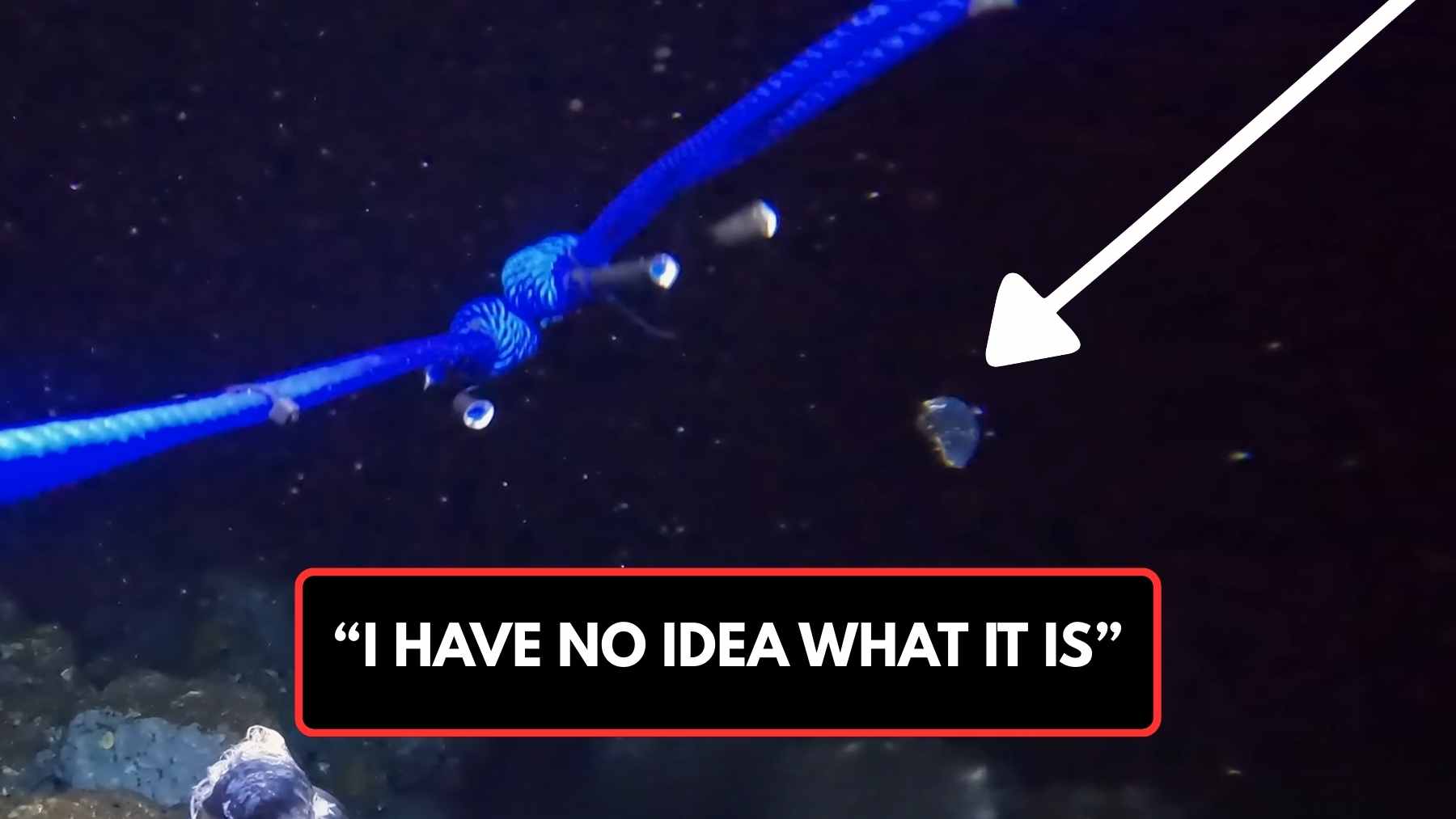

Now imagine that, but the “other dimension” is 200 meters (656 feet) down on the ocean floor. That’s basically the setup behind new deep-sea footage from YouTuber Barny Dillarstone, who has been lowering underwater camera rigs across the Indo-Pacific hoping to spot something “new to science.” Earlier this year, he sent a baited camera down into the Bali Sea in Indonesia on two consecutive nights.

When he recovered the footage, it showed the kind of nocturnal marine lineup most of us only see in documentaries. And then there was one animal that, according to Dillarstone, even the experts he consulted could not confidently identify.

Where did the Bali Sea camera drop happen, and what showed up at 656 feet?

Dillarstone’s setup was simple in concept but difficult in execution: a camera rig sent down after dark to watch what emerges in deep water at night. The footage he recovered included rarely seen nighttime species like conger eels, nautilus, moray eels, duck-billed eels, spider crabs and carrier crabs, along with other deep-sea animals that tend to stay out of sight.

One sequence, released in late July, has drawn significant attention: the camera picks up a deep-water ray referred to as a “stingaree”. In the video, Dillarstone says, “Stingarees aren’t really supposed to be in Indonesia,” pointing to why this sighting raised eyebrows in the first place.

Why would a stingaree in Indonesia raise red flags for marine biologists?

Stingarees are typically found in parts of the Indo-Pacific, especially off eastern Australia. However, their recognized range does not normally include the waters where this footage was filmed. Animal ranges are like nature’s address book, and when something pops up far outside its known territory, scientists want to know if it’s a rare visitor, a misidentification, or something else.

Dillarstone also points to other stingaree-related context in the region: he says the Java stingaree is considered extinct, and the Kai stingaree has only been documented from two juvenile specimens caught off eastern Indonesia.

Separately, an assessment led by Charles Darwin University reported that the International Union for Conservation of Nature, known as the IUCN, declared the Java Stingaree extinct as part of its Red List updates. The IUCN Red List is a global system that ranks extinction risk, acting as a central database from “least concern” all the way to “extinct.”

Could this be “new to science,” and what does that phrase actually mean?

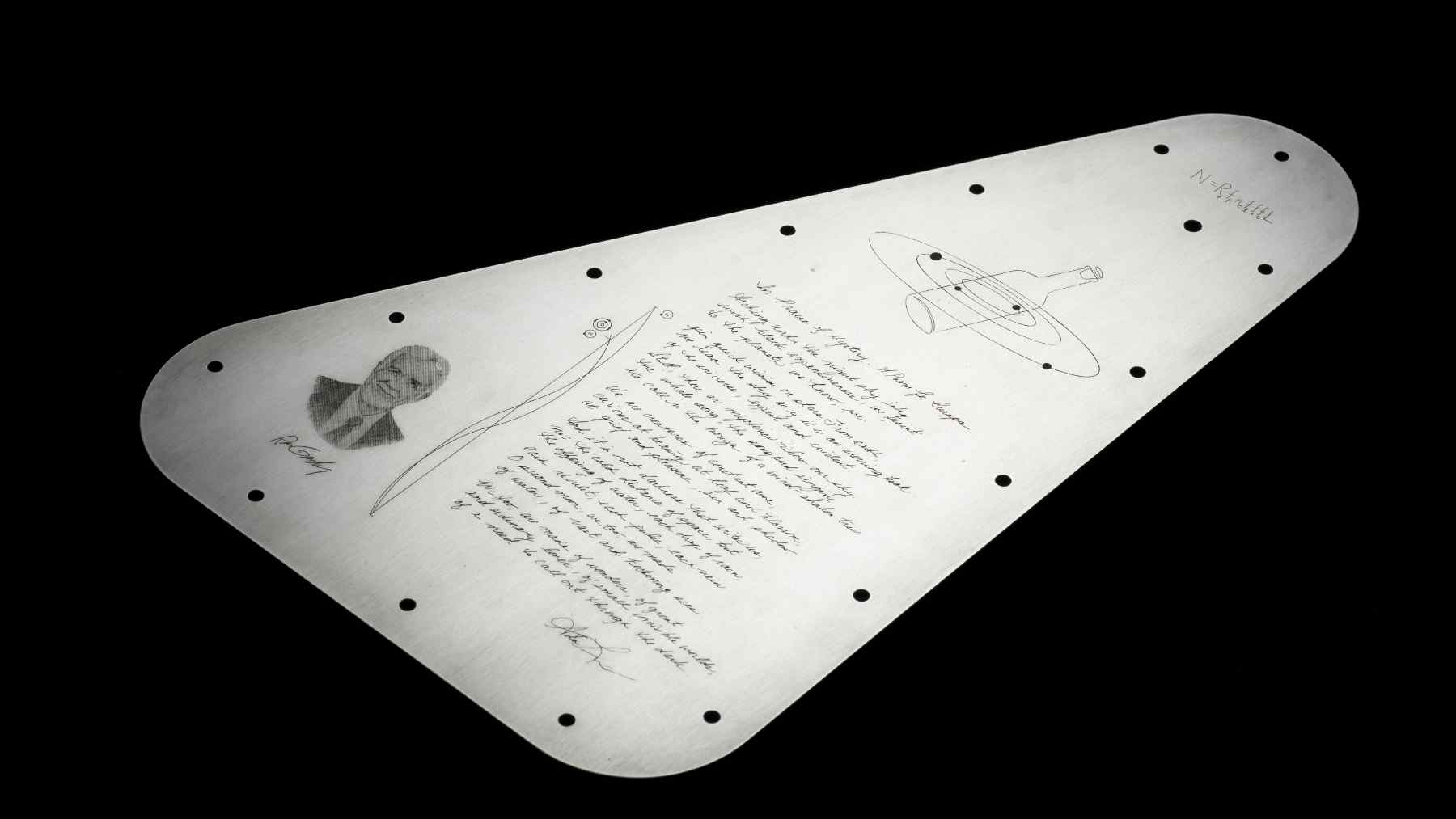

Dillarstone’s goal is to record a species that is “new to science,” meaning a species that has not been formally recognized and documented by researchers.

He says that biologists he consulted were unable to identify the animal and suggested it may represent a species not previously recorded in that area.

That’s where the slow, paperwork-heavy side of discovery kicks in. A project called The Ocean Census, launched by The Nippon Foundation and Nekton, notes that identifying and officially registering a new species can take up to 13.5 years.

In other words, even when something looks “new,” it can take a long time before it becomes officially part of scientific records, because it requires formal description and publication.

What can regular people do if they film unusual wildlife or think they found something rare?

It’s tempting to treat a surprising animal sighting like a viral moment first and a science moment later. But if you want your footage to actually be useful, a few practical steps can make a big difference, especially when location and conditions matter. Here’s what to do if you capture unusual wildlife footage, underwater or otherwise:

- Write down the basics right away: date, approximate location, depth (if known), and any details on water conditions you can reasonably describe.

- Avoid disturbing the animal or habitat. Don’t return to “get a better shot” if that risks harm.

- Share the footage with a credible local expert, like a university marine biology department, a museum with a marine collection, or a recognized research group.

- Be careful with strong claims online until experts weigh in. “Rare” and “unidentified” are not the same thing.